Thursday, 27 June 2013

Distance 34 km

Duration 8 hours 35 minutes

Ascent 784 m, descent 1045 m

Map 163 of the TOP100 lime-green series

Topoguide (Ref 7000) Le chemin de Régordane

For once we had an early start, just after 6:30 am. Our plan to join the GR at the col worked brilliantly and we were soon going down the other side on what was obviously the real Régordane.

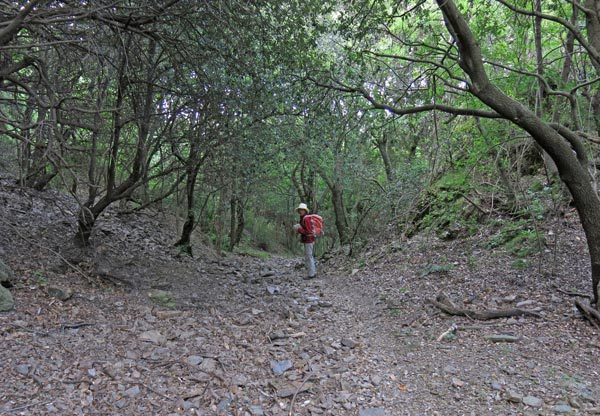

This section was too steep to have been taken over by the highway and had been left to decay under a canopy of dark, twisted, slightly sinister trees. Broken paving lay about in drifts, but the original engineering could still be seen – embankments and cuttings forming a wide, well-graded surface.

In its present ruined state it was slow to walk on. We did not like the look of an abrupt little deviation up the embankment, so we stayed on the main pathway and soon emerged from the trees into the village of St-André-Capcèze.

The meadows between the houses and the river (the Cèze) were dotted with vegetable gardens, each with a row of flowers amongst the culinary produce.

We continued on a small road that crossed one bridge, then another, and came to the bigger village of Vielvic. This was where we hoped to have our second breakfast, at the bar mentioned in the Topoguide.

The narrow main street (indeed the only street) was lined with handsome stone houses, and at the end of it we found the bar, which looked quite new.

The only trouble was that it was still closed at 8 am, despite the bustle all around it, as people delivered their children to the school bus.

It was only about three kilometres to the next possible breakfast stop at Concoules, so with a last wistful look at the bar, we set off again along the D51.

Having crossed a bridge, (the unimpressive border between the departments of Lozère and Gard) we immediately left the bitumen for a stiff climb that cut off several loops of the road and brought us to Chambonnet, which was little more than a château, much restored, at the top of the rise.

Beyond the château we went down to rejoin the main road, but stayed on it for only a few hundred metres before taking another steep, stony short cut up through the forest.

A few twists and turns, fortunately well marked, delivered us to the high village of Concoules.

We wandered along the street without seeing anything resembling a bar, but there was a sign – “Auberge, Vival”, pointing down a long tree-lined staircase to the highway.

With some reluctance we made the descent, only to find that the auberge did not open until 11:30 (it was 9 am). This was highly annoying. We could have bought lunch supplies at the Vival, but decided to get them later, which turned out to be a big mistake.

Back up the staircase, we filled our bottles at a fountain and continued on the GR.

The best thing in the village was the church with its octagonal chevet and its comb-shaped bell wall, so typical of the region.

As at Prévenchères, there was only one bell left in the comb, of the original four.

On the next section we really needed the GR signage, or we would never have found our way through the mass of forest tracks that rose and fell, ending with a sudden descent into the top streets of Genolhac.

The town clung onto a steep hillside, with the great bulk of Mount Lozère rearing up to the west.

The streets were narrow but full of life and we were very pleased to arrive after being twice deprived of morning coffee.

Without difficulty we found a boulangerie and then got ourselves to the main square, where there was a bar. We could have sat outside under the plane trees, but as usual, it was too cold for comfort so we retired to the interior and admired the flowery square through the glass.

It was at this point that Keith realised that he no longer had his warm top – it must have fallen out of the back of his pack, where he had put it earlier.

While we were enjoying our pastries and the first coffee of the day, a dignified, silver-haired man came up to our table and introduced himself as the president of the local group responsible for the upkeep of the Régordane.

He had guessed that we were walking it and was interested in having our thoughts on it once we had finished, so he gave us his card (which we later lost, to our great dismay).

We sat in the bar listening to his tales of life in the Cévennes in the old days. His family had been Protestants, as were most people in the district, and were persecuted constantly up to the time of the Revolution. “Then we got the Rights of Man, and things improved”, he said.

He was very interested when I said that I had read Les Fous de Dieu (a story about this persecution by Jean-Pierre Chabrol, a famous local writer).

The origin of the name Régordane is apparently still a mystery – it was the name of the hero’s route in one of the earliest chansons de geste, and may have referred, in the Occitan language, to the chestnut trees that covered the mountains. On the other hand, it may have come back with the crusaders from a castle in Syria with that name.

By the time he left, with courteous handshakes, an hour had passed. Reluctantly, we shouldered our packs and set off to the bottom of the town, where we took the road over the railway line (in these parts the railway line is as much in tunnels as out of them).

A kilometre or so further on, the GR left the road and crossed an original Roman bridge, but for some reason it was barricaded off and we had to use the modern concrete one to get over the river.

The small road climbed through the trees and arrived at the highway (the D906), where the GR immediately plunged down into the forest on the other side. The wide, boulder-strewn path had all the attributes of the real Régordane.

At the bottom of the slope we joined a small bitumen road (also no doubt the real Régordane) beside a river and came to the single-street hamlet of Pont de Rastel, a canyon of stone with low, arched doorways and shuttered windows. This was where Jean-Pierre Chabrol grew up. All the houses on the river side had gardens stretching right down to the water.

Over the bridge was a big square building, the handsome remains of a nineteenth-century silk factory which had used a water wheel to spin the thread. The road wandered on beside the river until it came to a tributary, where it turned, but we crossed a footbridge and kept going along a path by the water.

Two wet boys in swimmers were lying on towels on the stony beach opposite, under a sign saying “Bathing Forbidden”, and we exchanged friendly waves. We were impressed with their hardihood on such a cold day.

We went through a patch of tall bamboo, part of the grounds of the château of Montjoie, whose conical turrets could be glimpsed through the canes, and emerged behind the houses at the edge of Chamborigaud.

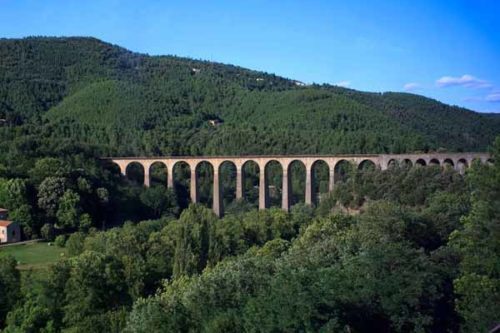

Ahead of us down the valley we saw a high, curving line of arches – the railway viaduct. To save money, it had been built with such a tight bend that it could only be crossed at very slow speed, but it was certainly spectacular.

Like so many of these riverside Cévenol villages, Chamborigaud consisted of a single long street lined with houses, but the highway bypass, around the back of the houses, had seduced all the shops and cafés away, and now had an amazing number of restaurants and bars, all doing brisk lunchtime trade. We stopped for coffee at one of them, and sat outside on a vine-draped terrace, although it was really too cold.

There was a camping ground at Chamborigaud but we decided to press on up to the col at Portes, to shorten the following day’s walk. It was only 1:30 pm so we had plenty of time.

From the old main street, we went under the highway and up beside the river, which was no longer the Luech that we had been following, but a tributary. At first we passed houses and neat vegetable gardens, but as we rose these got scarcer, and just after going under the railway overbridge, our little potholed bitumen road became a dirt track.

We were now in thick forest, seemingly far from civilisation, although we knew there were roads on both sides of us. The path was steep but well-marked.

We crossed a newly built footbridge and continued until we came to a fork in the track with no GR sign at all. We realised that we had not seen one since the footbridge, so, thinking we must have made a mistake, we turned back.

This always goes against the grain, but luckily, on the way down, Keith noticed a GR sign. Once again we went uphill to the fork, where this time we managed to find the missing GR sign hidden behind a leafy branch (which we broke off).

With renewed vigour we set off, waving merrily to the people in a house across the stream. As we ascended, the track actually merged with the stream bed and we found ourselves hopping from rock to rock or sloshing through the mud at the edge of the water, but before long we emerged onto the highway, our old friend the D906. We had never been far from this road since we left Langogne. Indeed it was the modern equivalent of the Régordane, with the steepest bits realigned.

At the intersection with a side road there was a picnic area, pleasantly surrounded by grass and trees, a contrast with the tangled wilderness of the hillside. We stopped here for a drink of water and a snack. We had bought bread in Genolhac, but had forgotten to get any other supplies, so we made do with a bit of left-over sausage.

The GR cut a corner up to the village of la Tavernole, and after crossing the road, went down a little street and out on a leafy path under a canopy of massive chestnut trees. We continued to climb, crossing the road a couple more times and occasionally even dipping down.

The track looked ancient, with mossy stone walls in places, and surprising vestiges of the former coal industry, which began in mediaeval times and lasted until the twentieth century. Buried in the forest beside the track was a sloping stone chute, used for loading coal, and other abandoned, rusting bits of machinery.

It was a beautiful walk but we were getting tired and we were glad when the forest gave way to fields and we saw the legendary castle of Portes in front of us on its grassy knoll. Soon we were back on the highway in the village.

Portes was living proof that proximity to a tourist attraction does not necessarily make a village prosper. It was a sorry-looking place, little more than a few dilapidated buildings flanking the highway, with a mairie and church at one side. According to the Topoguide the place had two gîtes, so we asked at the bar, where an old fellow pointed up behind the church.

When we found it, the gîte was locked but there was a sign on the door directing us to the mairie. The mairie was also locked, with a sign on the door setting out its opening hours. Quite clearly it should have been open, but no amount of knocking could bring forth a response, so we went back to the bar. This time we showed the barman the entry for the other gîte and he laughed – it was five kilometres perpendicularly off the track and principally for horse-riders.

Defeated, we sat down outside the bar, with glasses of Orangina, to decide what to do. After a while the cold, sweet liquid revived our spirits and we felt that we could face an extra 4.5 kilometres to l’Affenadou, where there was another gîte.

We asked the friendly barman to refill our water bottles but he said we would be better off with water from the natural spring on the bend of the road (and we were).

It was all downhill to l’Affenadou. The track was wide and pleasant and all went well until I decided that we could save time by going down the highway for a few hundred metres.

When we got to the place where we wanted to go back to the track, we found that it was barred by an impenetrable fence, so we had to continue on the road, which did a major switchback before descending to the river.

Just over the bridge, a dirt road went off to the left and it would have been nice if there had been a sign pointing to the gîte, as it turned out to be along that road, We only found out after trudging into the centre of the village and asking someone. When we finally got onto the road, we walked and walked without finding the gîte.

We crossed the river again next to a ruined bridge (probably a relic of the old Régordane), went past a scattering of houses and were about to give up when we saw it, at the very end of the road.

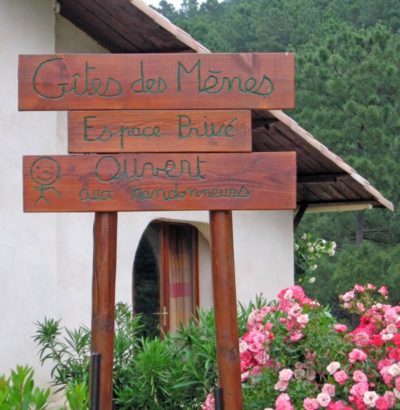

It was a delightful sight with its clean white walls, dark joinery and immaculate gardens. The sign announced that it was open to walkers and we rushed to the door, only to find it locked.

We tried all the doors in vain, and eventually had to admit that we were not going to get in. It was a great surprise to us that walkers’ gîtes would not be open. In all our previous experience, they opened at 4 pm and had a resident guardian who provided a cooked meal and breakfast, as well as a bed.

Gloomily we prepared to pitch our tent on the beautiful lawn and starve for the night. We had a phone number for the owner, but no phone.

Then we remembered that we had seen a couple of people at a house further down the road, so we walked back and asked a woman to ring the number for us. She obligingly did so and I ended up talking to the owner, who could have been in Paris or anywhere.

After chastising me gently for not booking ahead, she very kindly and trustingly told me that the key was in a little grey box near the back door, and gave me the entry code.

I needed a pen to write it down and I thought the neighbour woman was offering me one, but it turned out to be her e-cigarette!

Soon we were inside and gratefully unpacking. We were grateful for the hot showers, grateful for the electric light, grateful for the beds (there were ten to choose from in the long dormitory), and grateful for the table and chairs to sit at.

We had nothing to eat beyond the remains of the baguette and a few slices of sausage, and the cupboards were entirely bare, but there were tea bags and an electric kettle, so we had several cups of tea with our tiny meal and thought ourselves blessed.

We had nothing to eat beyond the remains of the baguette and a few slices of sausage, and the cupboards were entirely bare, but there were tea bags and an electric kettle, so we had several cups of tea with our tiny meal and thought ourselves blessed.

Previous day: La Bastide-Puylaurent to Villefort