Tuesday, 9 June 2015

Distance 11 km

Duration 2 hours 35 minutes

Ascent 146 m, descent 146 m

Map 174 of the TOP100 lime-green series

Fresh from a couple of days of comfort and leisure with our well-placed friend in the Pyrennean village of Arles-sur-Tech, we arrived at Port-la-Nouvelle on the local train from Perpignan.

We remembered this village from two years earlier when we had abandoned our walk at this point because of a heatwave.

Naturally we needed to build ourselves up before setting off, so although it was in the opposite direction to the day’s walk, we strolled along beside the canal to the bar on the church square.

Before ordering our coffee, we asked where the nearest boulangerie was, and were told that there was none, only a supermarket.

It was hard to believe that a French village with several bars could lack a boulangerie. However, at the Huit à 8 we got half a baguette, which made a good little snack to accompany our coffee, especially with the butter and jam that we had saved from the plane.

This year we were a party of three – Keith, me and a small bear by the name of Bert, who was representing the younger members of the family.

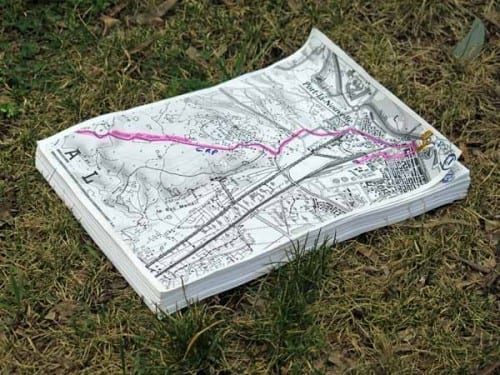

Another novelty this year was that we had a complete set of home-made maps, forming a dossier as thick as a small telephone book. Each page covered only about three kilometres and had a pink line to show the route.

We (principally Keith) had laboured over these for months and had improved them since last year, when we had carried a few, but still relied on TOP100 maps for the most part. This time we had no maps or guides apart from our own.

The enormous scale of these maps (10 cm = 1 km) made them very satisfying to use, as we made such quick progress across them, and every tiny detail was marked.

Not that we were likely to get lost on the first part of the walk – it was marked as both a GR and a GRP, although we were not sure which GR it was supposed to be. It was also the Cathar Way.

We started out not long before midday, and having crossed the railway line and the main road (the D709), we took a wheel track up a low rise covered with scrub and small oaks – the landscape known as the garrigue, as parched as Australian heathland and just as aromatic.

From this slight elevation, the surrounding scene had a damaged look – to the right the scar of a gypsum quarry with a feeder belt to a cement works, behind that the clustered silos and tanks at the mouth of the canal (it was one of the biggest Mediterranean ports in France), various roads and railway lines, and what looked like oyster beds beside the lagoon.

This part of the Mediterranean shore is a flat, sandy, treeless waste hemmed in by swamps and lagoons, and the streets still had a frontier look about them, even though the village had presumably existed since the Canal de la Robine was built in the late seventeenth century. (It must have been easy to build, as it followed an earlier bed of the Aude river, which had shifted its course since Roman times).

But up here we felt remote from all that, as we swung along with the spicy scents of the garrigue in our nostrils. It was delightful to be setting off on another French adventure.

The dirt road shrank to a stony path and at the top of the rise we came to a line of wind turbines, impressively large up close.

On the other side of the ridge, away from the sea, the countryside was greener, and beyond a second line of wind turbines we could see the bony flanks of the Corbières rising abruptly from the plain.

We descended sharply, winding down a hillside of small pines, and parted company with the Cathar Way just after joining a small bitumen road.

This continued down to the big Sigean bypass road, where we were able to walk straight across a bridge, while cars had to deviate onto the highway.

After that the land flattened out and we soon arrived at the raw new houses on the edge of the town, and zig-zagged through them to the main road (the D2009), where we knew the camping ground was.

The only trouble was that the entrance of the thing had moved since our map was drawn, and we had to back-track down the road before we found a way in.

When we did, it did not look inviting – an enormous expanse of dead grass with a couple of buildings and a few straggling trees. There seemed to be no other campers.

At the office we paid €17.20, which we thought exorbitant, and were directed to the most desolate, lumpy part of the whole place, amongst thistles and half-dead shrubs.

Having had showers (for which lukewarm was perhaps too charitable a description), we decided to move to the relative luxury of the mown grass near the shower block, on which a circle of canvas cabins sat amongst poplar trees.

A couple of the cabins were actually occupied, to our surprise. This was much better and we enjoyed an afternoon of inactivity in the shade. It had been a very short day’s walk, really only half a walk, but a good warm-up for our legs.

At about 6 pm we felt the urge to visit the town. Half a kilometre or so up the main road we came to a complicated intersection with shops on all sides. Facing the church was a large bar, suitably named la Rotonde, wrapping around the curve of the road. The outside was adorned with palm trees and umbrellas, and the tables were full of drinkers, a cheery sight. (By contrast the interior was dark and positively baroque, with chandeliers, mirrors, murals and plaster statues.)

Before joining the drinkers, we looked around for somewhere to dine later. There was not a lot of choice. The most promising looking place, le Potager, was closed on Tuesdays, and the one next to the bar, le Patio, seemed expensive, so we decided on the galetterie, le Breton du Puit, a bit further along.

Then we settled down outside the bar. There was a low wall planted with flowers separating the terrace from the road and it provided hurdling practice for the fitter members of the community, including our stocky, black-bearded waiter who came flying over from the street to take our order.

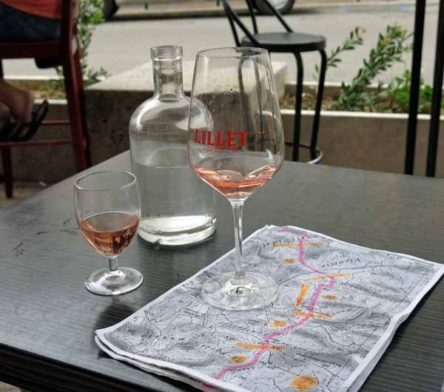

With a pastis and a rosé in front of us, we savoured the resumption of our old habits in France, and enjoyed the sight of the passing locals shaking hands and ritually kissing each other, and the sound of the language in our ears, with its southern twang.

At 8 o’clock we were ready to dine and went back to the galetterie, where we were the first and only customers for the evening. The room was bright and elegant, with framed picures of Brittany on the walls.

Our host was a tiny, rotund, chatty fellow, a native of Quimper, who had retired to the south after a lifetime in some stressful managerial position which required him to take two plane flights every week. He declared that he would never get on a plane again, and was appalled when we said that the flight from Australia usually took more than 24 hours.

To begin our dinner, we shared a salade de chèvre chaud, and it was a fine example of this classic dish.

The crusty rounds of goat cheese, each on its little raft of toast, were molten inside and rested on a mound of salad that looked as if it had been picked a few minutes earlier, presumably by our host’s wife, who did the cooking behind a curtain at the back.

Meanwhile we tried on a beribboned Breton beret provided by our talkative companion.

Then we had sarrasines, which Monsieur explained were subtly different from galettes – they were both buckwheat pancakes, but were folded in a different way.

Keith’s contained ham and cheese while mine had mushrooms. With them we had some wonderfully leathery bread and the rest of our half-litre of wine. Altogether it was a very enjoyable evening.