Thursday, 18 May 2023

Distance 28 km

Duration 8 hours 35 minutes

Ascent 105 m, descent 210 m

We woke to the light patter of rain from the open window and by the time we packed up and left the hotel it was teeming.

We sprinted across to the brasserie and huddled under an awning until the place opened, which was not at 6 am as had been promised by the geriatric hotelier, but at 7.

There were a few other people waiting with us, including a bossy, garrulous ex-military man from Sisteron. He spoke English after a fashion, and was at pains to demonstrate it, refusing to acknowledge that I was speaking to him in French (also after a fashion, admittedly).

He was probably well-intentioned, and pressed his name and telephone number on us in case we found ourselves unable to cope with France, although we had mentioned that we had done long walks in his country many times in the past.

He then insisted on telling us his views on the world, in particular his prediction that World War III would break out later this year, and that it would be a nuclear war.

We did not really want to hear this so early in the morning, and when the doors of the bar finally opened, we made sure we sat far away from him .

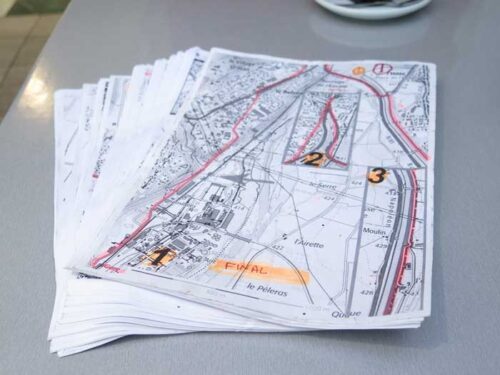

When we were sitting comfortably in front of large steaming coffees and had extracted our great wad of home-made maps for the first time, he annoyed us further by coming over to our table and instructing us in French manners, pointing out that we had not said “s’il vous plaît” when asked by the barman where we would like to sit.

Escaping from this sanctimonious pest, we set off in light drizzle, swathed in our capes.

We crossed the Durance and the canal, then followed a path beside the canal, flanked by orchards and vines, which led to the first houses of Malijai.

It was a pleasant walk despite the rain, and we were delighted when we came to a boulangerie, which was also a bar.

By the time we had enjoyed another round of coffee and croissants, the rain had stopped. Things were looking up.

We remembered this village from an earlier walk, and admired once again the pink façade of the hotel (now the Mairie) in which Napoléon had spent the night on his triumphal way from exile on Elba to his hundred days of renewed glory in Paris.

In the lanes around it, the houses were painted all sorts of colours, haphazard but charming.

Behind the Mairie, past some elderly plane trees that were probably there when Napoléon was, we crossed the river and pursued a track beside the canal through sodden fields and copses of trees.

Our boots and socks were already soaked so it made no difference.

When the canal disappeared into a tunnel in the hillside, the path continued, and suddenly we were under the looming spires of les Pénitents, a line of frighteningly tall, unstable-looking columns composed of loosely compacted round pebbles polished by millions of years under moving water of some sort. Walking under them was quite awe-inspiring, even intimidating.

When we were most of the way along the track, Keith tripped and sprawled on the ground, bruising his ribs a bit.

He should have been using his pole but had not thought of it, never having had one until a couple of weeks earlier. Fortunately, by that time we were close to the village of Les Mées.

It was Ascension, a public holiday, and the earlier rain had stopped long ago, and the air was surprisingly warm, so the good citizens of the village were out in force and we lost no time in joining them.

For the first time we felt the joy, familiar from past years, of relaxing with the locals in a tree-lined square.

Little did we know that that it would almost be the last time, and we would have laughed off the very idea, poor fools that we were!

When we were leaving les Mées we saw the remains of one of the Pénitents which had collapsed during a storm a few years before and demolished a house.

We were amazed that all the other houses in this row seemed to be still occupied, presumably by people with nerves of steel.

After a while we struck upward from the road and found the canal, newly emerged from its tunnel. There was a stony dirt road beside it which we followed.

The landscape was bare and featureless but we kept track of where we were on the map by counting the bridges.

Meanwhile the sky darkened, the sun vanished and soon we were enveloped in a misty drizzle. We put on our capes as the rain increased, and trudged on.

The maps were in a plastic sleeve but they still got wet and threatened to disintegrate. After a long time we came to the place where we would leave the canal and join a small dirt road nearby.

It was this point that we realised that the short distance on the map between the canal and the road was actually a precipitous drop, which we had to slither down as best we could. The road at the bottom was flooded, of course.

We came to a sign to “Les Oliviers” camping ground but I could not check whether it was the one that we were heading for, because we had made the maps too narrowly focused on our route, i.e. on the canal, and the other camping ground (and indeed most of the surrounding features) had been cut off.

This was a mistake that was to haunt us for the duration of the walk. Anyway, we were so drenched by then that we decided not to camp (this turned out to be a mistake).

At last we reached the outer streets of the town of Oraison and looked forward to finding a hotel or a gîte in which to spend the night.

There were not many people about on this rainy afternoon but we asked everybody we met and nobody knew of a hotel in the town.

At length we arrived at a square with a couple of bars and went into one to enquire. The barman took in our soaked and bedraggled state with sympathy, but could not think of a single place, so we disconsolately ordered coffee and went out to drink it in the draughty, streaming plastic enclosure outside. Why did we do that? Self-flagellation?

After a while the barman came out to tell us that one of his customers had remembered that there was indeed a hotel nearby, but it was an hour’s walk away.

This did not deter us – we had no other options, after all – so the barman booked us in and, with many thanks to him and all the loafers in the bar, we set off to La Grande Bastide.

As we started walking, we realised that we had not taken a single photo of Oraison, such was our discomfort, anxiety and general misery. This realisation was the least of our concerns at the moment.

No more than fifteen minutes later we arrived at the hotel (a good example of the locals having no idea how long it takes to walk anywhere – they evidently never do it themselves).

It was beside a raw-looking new housing estate and looked equally raw itself, although surrounded by mature trees. We imagined a graceful old farmhouse being bulldozed to make way for it.

Inside, a worried-looking man at the desk escorted us down a long, silent corridor to our room, which had all the attributes that we needed, chief among them being a roof. However its charms were mitigated by our recent discovery of the price, shocking to habitual campers like us – but we were not complaining.

Later, after showers, a change into dry clothes and a short rest, we went to the dining room, which was vast but empty, except for two mouse-like couples who were feeding quietly at far-flung tables (this paucity of guests probably accounted for the worried look on our host’s face).

We did not add to his joy very much, as we had only two dishes and a half-litre of local red wine.

Keith had a creamy chicken dish with pasta and I had a crunchy salad. Of course we ate a lot of bread as well, and polished off all the wine, so it was quite a good meal.

We had walked about 30 kilometres, mostly in the rain, and it was the first day of our expedition, so when our heads hit the pillows we remember nothing more.