Thursday, 17 June 2010

Distance 22 km

Duration 4 hours 40 minutes

Ascent 100 m, descent 95 m

Map 56 of the TOP100 blue series (or Map 160 in the new lime-green series)

Topoguide (ref. 6542) Sentier vers Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle via Vézelay

From our window we could see a sky full of cold, hurrying clouds, but at least it was not raining. We had showers, just because we could, and descended to the dining room for our hotel breakfast.

Before I went down I plastered glue on my flapping soles and left them held apart by a toothbrush and a pen. I was using the sort of glue that needed to be pressed together once the glue had partially dried.

Breakfast was entirely delightful. The sporting lads were just finishing as we arrived and the room was thinly occupied by elderly couples like ourselves.

With our customary enthusiasm we cleaned up everything on the table – orange juice, fresh bread and croissants, butter, jam, coffee and hot chocolate, all of which combined to give us a feeling of strength and optimism as we set off.

Although we had no map to guide us, we felt sure that we could cut many kilometres from the day’s walk by heading west, crossing the Garonne and following the road south along the river flats, as we had done yesterday, keeping our feet out of the mud at the same time.

The GR did not cross the river initially, but instead climbed high over a plateau and down to meet the river at Port-Sainte-Marie.

We had no TOP100 map of the area, and the map in the Topoguide only extended a few hundred metres to the west of Aiguillon, so there was an element of wishful thinking in our plan, but it would be an adventure, no matter what happened.

Descending to the station, we crossed the line by an underpass and turned left onto the small D642. There was a bit of commuter traffic on the road (it was 8:30 am), and even more when we merged with the D8 and headed towards the river.

To our surprise, there was quite a large town, Saint-Léger, just over the bridge. The Garonne swirled ominously beneath our feet, its waters mixing with the turgid brown of its tributary, the Petite Baïse.

We had not gone more than a couple of blocks in the town when we came to a turn-off, a small road through the fields beside the river. It was the D642 again, which seemed a good sign.

Trucks lumbered past with great loads of sand, but as soon as we were clear of the entrance to the quarry we had the road to ourselves.

Half an hour later we had another surprise – we came to the Lateral Canal of the Garonne, where pleasure boats were tied up at a landing stage.

There was a bar-restaurant, firmly closed, but signs pointed over the bridge and up the hill to Buzet-sur-Baïse, a village that we had never heard of, promising shops and refreshments.

After 26 days of walking along rivers and canals, we had forgotten about hills and our legs were protesting by the time we came to the long main street of the village.

We asked a woman road-sweeper whether there was a bar, and she replied in a delightful southern twang, that there was, and it was not too far – “pas trop lueng”.

When we got to the far end of the street, we found that coffee was being served at the épicerie, which doubled as a bar. The only other shops were a boulangerie and a wine merchant, and there were two pleasant looking restaurants which were not yet open.

We sat outside in the shade of a mangled plane tree, and watched four council workers trying to put up a new bus shelter across the road. It seemed to require a lot of oratory and gesticulation.

It turned out that Buzet was the centre of quite a famous wine region, specialising in full-bodied reds. As we set off again on the D642, we entered a landscape of vines.

Before long our little road crossed the autoroute and, a bit further on, the disused railway line, which we then followed for a couple of kilometres, with the river Baïse on our other side. We had now walked our way back onto the maps in the Topoguide and knew that we were approaching Vianne.

The road was flanked by small market gardens and cottages, but in the distance we could see a remarkable assemblage of towers. As we got closer they resolved into a grand portal flanked by a high wall, with circular towers at the corners.

Vianne was a beautifully preserved bastide, set out on a rectangular grid with a portal in the middle of each side. Inside the wall, we came to a central square, from which it was possible to see all four portals at once, a useful attribute in its early years of turmoil.

We found out that the village had been founded in 1284, jointly by the Duke of Aquitaine (otherwise known as King Edward I of England) and Jourdain de l’Isle, an unsavoury character who had inherited the land from his aunt Vianne. Her family had been the traditional feudal masters of the area.

There was already a village there, with a weir and mill on the river, and a church. In the new town, each householder had an allotment of land 12 metres by 24, in which to grow vegetables, as well as a stake in the broader agriculture beyond the walls.

Land was rented from the lords, who also received taxes on all sales at the market, but the inhabitants were free men, not serfs.

The rich lands of Aquitaine were coveted by invaders of all stripes, which was why the village was fortified, even before the outbreak of the Hundred Years War. The English king felt his lands in Aquitaine threatened by the nearby French bastide of Lavardac, which had been established a few decades earlier by the brother of king Louis XI.

During that war, it changed regularly between English and French hands until finally being ceded to France in 1442. It was a miracle that the wall survived the constant attacks.

There were so many sieges that the citizens often could not go out to cultivate broad-acre things like wheat and beef. Instead they lived on ducks and cabbages from their allotments, and in the process invented garbure, the famous soup of the south-west (or so the story goes).

Of course the village has been patched up since those times, but all the same, it had an authentic air, especially with the allotments still visible behind the houses.

To our eyes it was a good deal more “beau” than the average “Plus Beau Village“, although it was not among the chosen.

We settled down in the square, after a visit to the boulangerie, to build up our strength for the last few kilometres of the day. We were hot, but not because of the weather, only from our exertions.

Ominous clouds hovered overhead and we expected to be driven inside by rain, but we weren’t.

Tables were being laid for lunch all around us, but we were treated with typical French courtesy. We could have stayed there for the rest of the day without a flicker of impatience from the staff, but we had ground to cover before we could relax fully.

Our destination was the hotel in Lavardac. The only other accommodation, according to the Topoguide, was the camping ground at Barbaste, its twin town across the river, but it was too far out of the town for our liking. We would probably find ourselves having bread and cheese and cold water for dinner.

Leaving Vianne by the suspension bridge (a recent addition from the 1830s, replacing the ancient ferry), we found ourselves on the GR for the first time that day. The route promised to be delightful – the towpath beside the Baïse – but it was not.

Both the river and the towpath were flooded. We slipped frequently in the mud and at times feared that we would end up in the river.

In places trees had fallen across the track, forcing us to detour through nettles and blackberries.

Progress was slow, but at last we came to a sign of civilization – it was only a sewage plant, but we were very pleased to see it. Without hesitation we abandoned the GR and went up the access road into the streets of Lavardac.

Not much was happening in the main street at that hour. Unlike at Vianne, there was not much remaining of the bastide that had been so powerful in the middle ages, nor of its several previous incarnations.

Lavardac was occupied even before Roman times, as it was on the ancient trade route known as the Ténarèze, that linked Spain with Bordeaux and the valley of the Garonne.

This route crossed the Pyrénées a little to the east of the Cirque de Gavarnie, and proceeded north on descending ridges between Tarbes and Auch, keeping to the watershed between the Garonne and the Adour, before dividing, one branch going west towards Bordeaux and the other (the one Lavardac was on) continuing into the Garonne valley.

It was said that a traveller could get all the way from Spain to Bordeaux without ever crossing a bridge. This was important in medieval times, as every town charged a tax (the “octroi”) on goods coming in and out, and the easiest way to collect it was to put barriers on bridges. At Lavardac there was a bridge that could not be avoided, and the town became wealthy, but all that was former glory now.

We went into a bar and enquired about the hotel, to be told that it was about a kilometre away on the road to Nérac. We were just setting off on the road opposite the bar, which had a sign to Nérac, when some premonition made us go back and check, this time with the barman’s wife.

There were two roads to Nérac, she said, and that was not the one. We should continue down the main road, cross the Baïse, turn left and pass the old railway line to arrive at the hotel.

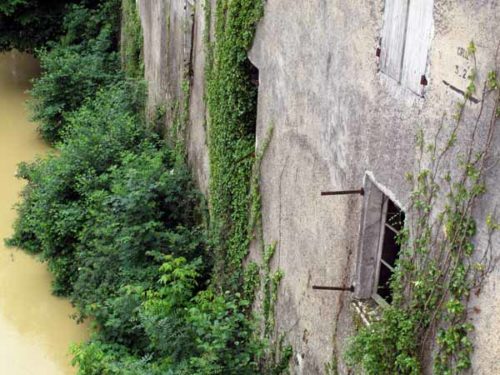

It was just as she had said. On the way we saw from the bridge an old sign marking the height of an earlier flood, frighteningly far above the present churning brown waters.

The hotel was a fine old vine-covered place, set in a garden, with its name, la Chaumière d’Albret, picked out in tiles on the roof.

We got a room for €39, with a shower but no WC, and confirmed that the restaurant would be open in the evening. It was full of lunch diners at that moment.

We lunched on bread and cheese in our delightful pink-walled room, after washing ourselves and our garments. All our walking clothes were caked in mud from our brief encounter with the GR.

My shoes were getting worse by the day, but I optimistically continued to dry them out and glue them together again after each stage.

About 8 pm we descended in our clean clothes to the dining room, which was not as crowded as it had been at lunch time. There was a solitary man and two other couples, one French and the other German.

Our hostess was proficient in German and spent a lot of time conversing with these guests. The room was pretty in a rustic way, with pink table napkins and coach lamps on the walls, as well as a grinning stuffed weasel and various gnarled branches painted black.

We took the €15 menu, which looked substantial enough to satisfy our appetites. The first course was soup (Spanish gazpacho, not the local garbure), and then we had nourishing salads laced with meat. Needless to say, Keith had steak to follow, while I had filet mignon of pork.

It was all delicious, but by this stage I had put away in my ever-ready plastic bag some ham, some pork and some butter. I had eaten so much bread before the food arrived that I was having trouble fitting in the four courses.

For dessert Keith had ice cream and I had cheese, which also ended up in my bag.

Previous day: Castelmoron-sur-Lot to Aiguillon