Tuesday, 24 June 2014

Distance 24 km

Duration 5 hours 40 minutes

Ascent 481 m, descent 326 m

Map 154 of the TOP100 lime-green series

We had arrived on the train the day before, and spent the night at the camping ground a little upstream from Figeac, where we had a wonderful restaurant dinner amongst the lawns and trees of the riverbank.

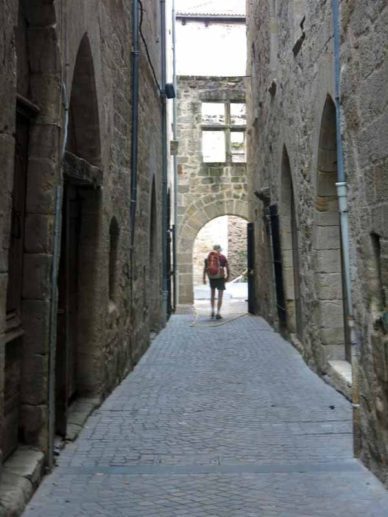

In the morning we left early, stopping to have muesli on a bench near the river, then walked back to town and crossed the first bridge into the network of lanes and squares that was old Figeac.

Everything was crooked – the streets, the walls, the rooves, the archways – and utterly charming.

In an alley we passed a gîte from which a pilgrim had just emerged, complete with walking poles, boots and huge pack. He set off towards the GR65, while we continued the other way.

Further on, we walked through a little well-like square that was paved from side to side with a large replica of the Rosetta stone. Its first translator, Jean-François Champollion, was born in Figeac.

The only fault we could find was the lack of bars. The streets, even the bigger ones, were as quiet as death and we were starting to wonder whether we would find anywhere for coffee before we left the town. Then suddenly we came to an old-fashioned café (the Café Lorrain) with its lights on and its glass door open.

There was a boulangerie opposite so we stocked up on pastries and went inside to join the few locals who were already propping up the counter, reading the paper, drinking coffee and conversing.

This delightful place made Keith declare, as he often does, that he was really a Frenchman who had been swapped at birth.

Much fortified by the coffee and croissants, we continued to the end of the street where we met the GR6 coming up from the river, and turned right beside a tree-lined stream, with houses on our other side.

There were placards on the trees protesting about their imminent removal to make way for a car park.

Then we were out in the country and climbing slightly on a narrow road. It took us half an hour to get to the end of the bitumen and in all that time we saw only one car (parked) and one bicycle (being ridden).

Beyond the bitumen the road became a wheel track and traversed a smooth emerald-green valley, which seemed remote from the world, even though we could see houses on the skyline and knew there was a main road not far away.

When the valley ended we laboured up a sharp rise to a road, then kept rising past a cluster of houses which presumably had a name, although we never discovered it.

Once again the GR took us off the road through the serene, orderly countryside, and only rejoined the road as we entered Cardaillac.

We had hopes of this place, as it was a Plus Beau Village, but at first glance it was hard to see why it had been so honoured.

The main street (which was also the D15) had a certain quaint appeal, but most of the shops were closed, in particular the bar. However we were told by a passer-by that there was a snack bar around the corner at the end of the street.

We found it out on the highway, a small timber-fronted building just in front of the towers of the château, which we realised was the reason for the village’s being plus beau.

On an information board we discovered that the building of the fortress began in the eleventh century, although the three remaining towers – two square and one round – were not built until the thirteenth. It was attacked repeatedly over the years, including once by Richard the Lionheart when he was passing by.

But our thirst was not so much for information as for coffee, so we made haste to the snack bar. Behind it was a small terrace prettily enclosed by stone masonry of various ages and we settled down there while a very old man with a limp and a hostile glare brought our coffee out.

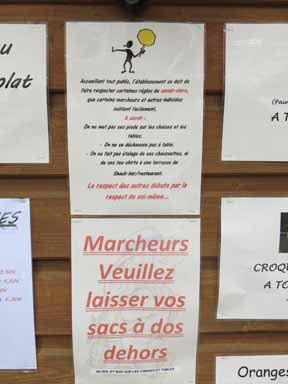

Looking around, we saw a multitude of notices pinned up on the walls and windows. Clearly the work of our host, they forbade guests from putting their packs on the tables, from taking off their boots, from spreading out their socks and T-shirts on the terrace, from eating anything that had not been bought on the premises (the last, a very un-French rule).

One sign informed visitors that they could be banned from using the toilets or the telephone, and refused free glasses of water.

Obviously the poor fellow had been insulted by the boorish manners of previous walkers. We hurriedly put our feet back in our boots and our packs on the ground.

Nevertheless it was a pleasant break and we said to ourselves that we were having a Cardaillac Arrest in the best possible way. Having beamed placatingly at the old man, we set off again.

The GR immediately dived into the ravine over which the château loomed.

The track was the ruined remnant of an former cobbled road, much scoured by rain and shaded by a deciduous forest. Once up on the other side, we meandered past a shining lake fringed with birch and pine, in which water lilies were flowering.

This was the artificial lake of the Sagnes. Then we joined a service road with patches of bitumen still clinging to it, which rose steadily through a pine plantation and delivered us onto a properly made road.

Our map of the GR route did not seem to correspond with the signs that we were following, but we pressed on regardless and soon reached a recognisable point, where the GR6 turned off the bitumen to climb to St-Bressou.

It was evidently an easily missed turn, as there was a big painted placard with an arrow. Further confirmation appeared in the form of two descending walkers.

Other walkers were rare, and we would have spoken to them but our attention was taken by three cyclists who were resting beside their machines.

They were genial Englishmen, on their way from St-Malo to Perpignan in the eleven days that they had available. Australians do not go to France for eleven days, we said.

They glided off and we decided, instead of struggling up to St-Bressou, to take the line of least resistance around the road, and meet the GR again as it came down the other side.

The road was completely quiet, with occasional farmhouses overlooking fields of wheat and lucerne.

By the time the GR rejoined the road, we were quite high and could see out over the blue haze of the land to the west.

A last climb brought us to a four-way crossing of roads and we started the long descent to Lacapelle-Marival on a precipitous, stony wheel track through a forest. This eventually became a little road.

We crossed the D15, and entered the town via a footpath that became a tunnel of greenery between two streams.

When we emerged onto a road, we could see the direction of the centre by the towers of the church and château.

On our way towards them we passed a Logis hotel, whose menu we looked at with a view to eating there in the evening, but we were aghast at the prices and hurried on. The bells of one o’clock sounded as we walked past the church and into the main square.

Not much was happening in Lacapelle-Marival at that hour. The shops were all closed, either for lunch or because of the roadworks that obstructed the streets.

The only people in sight were a couple of lost-looking pilgrims with a dog, and the roadworkers. One of the latter told us how to get to the camping ground by a short cut through a lane, and as we crossed the main road on our way there, we noticed a thriving bar – a good place for apéritifs later on.

The camping ground was a little way along the D940, next to the swimming pool. As is often the case on warm summer afternoons in France, the pool was closed, and so was the office that was shared by the camping ground.

We strolled in past tubs of flowers to a flawless, sweeping lawn graced by deciduous trees in full leaf, and dotted with campervans. We selected a relatively flat patch at the top and flung ourselves down in the shade. After the usual showers and clothes-washing, we had a little siesta, as the need for lunch had passed.

About 5 pm we rambled back through the laneway into town. The main square now had a few shops functioning so we bought some peaches for breakfast, some muesli and a roll of sticking plaster for future blisters, if we got any. The roll that we had brought with us had only one fault – it did not stick to anything.

At the Office of Tourism we got a brochure telling us that the château had been built by the lords of Cardaillac, the heavyweights of the district in the thirteenth century.

The site was at the intersection of two ancient trade routes, an east-to-west one from Lyon to Bordeaux and a north-to-south from St-Céré to Figeac, and the lords needed a fort here to extract tolls from passing travellers.

We also asked at the Office about where to get an evening meal, as we had seen nothing except the Logis hotel on the way in to town. After staring at the ceiling for a while, the woman remembered le Glacier, which was just around the corner, and not far from the bar to which we were heading.

As we walked past le Glacier, we called in and found a bent old woman in an all-enveloping apron sitting in the front room. She instructed us to come back at 7:30.

The Café des Sports was a fine place to spend the pre-dinner hour. The terrace was shaded by wide awnings and we enjoyed the bustle of other drinkers around us, most of whom were young and smoking.

At about 7:45 we presented ourselves at le Glacier, to find the dining room already almost full. We realised too late that it was not a normal restaurant, but probably the dining section of the gîte that we had walked past earlier. There was a set menu, a set price (€14.50 a head) and a set time, which we had overstepped.

The food was certainly reminiscent of the few gîte meals that we had eaten in the past. Madame brought a terrine, made by herself, to the table and we helped ourselves with alacrity, having not had lunch. The main course was thin steak with all the attributes of shoe leather, accompanied by cubes of fried potato.

This was followed by a cheese platter and finally a scoop of ice cream (we chose coffee flavour). It was not grand but we enjoyed it, and also the convivial atmosphere of the room, although we spoke to none of the other diners.

Back at the camping ground, we saw that the pilgrims with the dog had set up their tent near the entrance, but only the dog was to be seen. The humans were either out on the town or asleep – probably the latter.