Monday, 18 July 2005

Distance 23 km

Duration 5 hours 30 minutes

Ascent 496 m, descent 564 m

Map 57 of the TOP100 blue series (now superseded)

Driven by fear of another day of heat like yesterday, we were walking by 6:30. We took the road beside the river in preference to the GR for the first part, as the GR looked steep and crooked on the map.

At that early hour the road was as quiet as a mule path and the air was cool. Having passed a couple of hamlets, we arrived at Monteils, a pretty little place at the foot of a great forested bluff. Downstream of Monteils the river was enclosed in a twisting gorge.

The boulangerie was shut on Mondays, but we were gratified to find a bar open, a dark, low-ceilinged room with wooden tables, so we had coffee and some bread saved from last night’s dinner, making a fine second breakfast.

After that we took to the GR which had appeared in the village, and lost no time scrambling through pines to the top of the ridge. With the help of the red-and-white GR markers, we negotiated muddy forestry tracks and came out into open country on a tiny tar road which led us to Courbières.

This was a half-ruined hamlet on the brink of the gorge and looking out across an ocean of trees, we could see a line of buildings far away on the skyline. What we did not realise was that this was Najac, our destination. We were convinced that Najac was a riverside village, not a ridge-top one.

The GR then plunged through a tunnel of thick foliage towards the river. We could see from the map that it was going to cross the river and climb again before getting to Najac, so we thought ourselves very clever when we abandoned the GR halfway down and took a brambly farm track to rejoin the road. This would take us directly to the village, we thought.

Coming down the road, we saw the ruins of the château high on the hillside like a rotten tooth. At the river, all we could see was a railway station, a hotel and a camping ground.

Then we noticed a walking track with a sign pointing skywards to Najac, and our mistake became clear.

Just in case there was another camping ground closer to the village, we carried our packs up the steep, stony track and into the precipitous lanes of the town.

The village sits on a knife edge and half the streets are restricted to local cars, so that visitors must park at the top and walk down.

The streets are dedicated to tourism, with cafés, gift shops, food shops, hotels, fountains and lines of charming cottages.

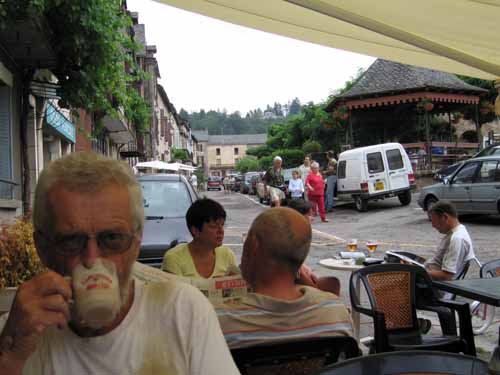

We joined the throng at an outdoor bar, which had a fabulous view down the street and across to the château, and had coffee and croissants. Was this a third breakfast?

Needless to say, there was no other camping ground on this narrow spine, so we descended to the river and set ourselves up on a piece of patchy grass for lunch, where a trout fisherman was casting his fly into the shallow stream.

The office was unoccupied but there were many other campers installed.

After a rest under a tree, we wandered over, in our fresh clothes and sandals, to the hotel, which was a large, old-fashioned, elegant place with a wide terrace looking up to the château.

We ordered afternoon coffee, which came with slices of brioche and chocolates. It was turning into a day of constant refreshment.

Various hearty foreigners in boots called in for drinks. We must have looked very idle by comparison, although we had been walking relentlessly for six weeks.

One glance at the exorbitant hotel menu persuaded us that we would be better off making one more ascent to the village.

The restaurant we chose had a terrace at the back hanging out over the valley, on a level with the ever-present château.

We had salade aveyronnaise, then aligot (the classic mountain peasant dish made of mashed potato, cheese and cream) with sausages and lamb cutlets.

The aligot bore more resemblance to plain mashed potato than to the wonderfully rubbery stuff we had first met in the Aubrac.

As it was a warm night, we had a carafe of rosé.

Keith finished off with ‘îles flottantes’, floating islands, a rather insipid French dessert.