Sunday, 23 May 2010

Distance 27 km

Duration 5 hours 55 minutes

Ascent 274 m, descent 264 m

Map 27 of the TOP100 blue series (or Map 135 in the new lime-green series)

We carried our tent, soaked with dew, out through the gate to a seat overlooking the river, and went back for all our other gear. The morning was clear and the first misty rays of the sun filtered through the trees, although without warmth.

The only other person awake was a woman with a sleeping child in her arms, sitting on another seat contemplating the quiet river.

In keeping with our usual habit, we left at 6:45. Years of walking in heatwave conditions had trained us to start early, even though this morning was cool.

We felt good about our first day’s walking and stepped out energetically for our second, over the link canal, then across the Loire on a long road bridge, presumably the replacement for the one blown up by the Resistance in 1944.

Setting foot back in Burgundy, we came to an intersection in the forest and took the small road to the right, which was also the GR31. No cars disturbed our tranquil progress and soon we came out of the trees, past a château to Tracy-sur-Loire, where the church was a dark, graceful shape against the eastern sky.

We skirted the few houses of the village on a grassy track beside the railway line, with the river on the other side. Before long the GR signs instructed us to leave this track and go up a muddy forestry road towards Bois Gibault. We were tempted to just keep going along the railway line, but previous experience had taught us to err on the side of caution.

In the main square of Bois Gibault were two or three bars, but none of them had bothered to open yet on a Sunday, so we pressed on, following the GR signs, and quickly found ourselves back on the railway line.

A bit further on, at les Girarmes, we climbed steeply to an airy summit clad in vines. Vines were first planted here in the 1870s, when the railway came through, and crates of table grapes went every day to Paris during the season.

It was a lucrative trade for the local peasants, but was cruelly cut short in the 1890s by the phylloxera outbreak that killed all the vines.

The descent was just as steep and we came down onto the sharply pitched roofs of les Loges.

After this the GR went up again, but we were tired of hills and preferred to go under the railway line and take the flat little road parallel to it until we got to Pouilly-sur-Loire.

At the bridge we turned in towards the town, but discovered that we had overshot the centre and had to go back a long rising way to find a boulangerie and a bar.

Looking back, we realised that we should have stuck to the GR, which, after an initial climb, came in directly to the main street of the village.

It was nearly 10 o’clock and we had been walking for three hours to get to our first coffee. We sat indoors to keep out of the hot sun, and had gigantic pains aux raisins with our drinks.

Pouilly is a famous wine town and we had intended to camp there on our first night, but we were glad we had not, as there did not appear to be much to choose from for the diner, unlike at Saint-Thibault. It seems often to be the case that villages which are famous for wine have little else to offer.

We were now back on the GR and we kept with it for the next section, which was a sandy track below the road in a riverine nature reserve.

Eventually we left the river, crossed a field and approached the village of Mesves-sur-Loire. The first thing we saw as we stepped up onto the road was a bar, always a beautiful sight, and we wasted no time installing ourselves there for another round of refreshment.

Just ahead in a dip in the road was a lovely-looking church and further on various shops and another couple of bars.

As we left town we came to the big bypass road (the bgN7) and crossed it at a complicated junction, which took us to a tiny local road separated from the highway by no more than a crash barrier. On our other side was a thick, wild wood.

Several kilometres later, at the next autoroute overpass, we crossed back and walked down a lane beside a château whose towers we could glimpse beyond the tall, crumbling wall and overgrown park. When we got to the edge of the riverine reserve, we turned left onto a rough wheel track under a powerline.

A bulldozer had recently been at work, widening the track by tearing out all the vegetation, including mature trees, and making it difficult to walk on, but we pushed on and in due course came to the bitumen road just as it converged on the river, at the entrance to la Charité-sur-Loire.

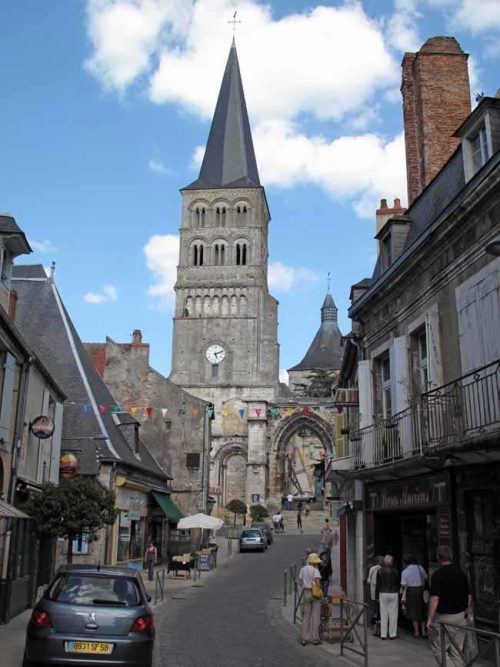

We walked in on a footpath between the road and the river, through lawns and flower beds, until we reached the bridge. The great steeple of the abbey loomed up on our left.

The camping ground was over the bridge on an island (just as it had been at Cosne-sur-Loire), and we arrived purple in the face from heat and exhaustion. It was 1:30 pm. It seemed an age before the paperwork at the office was done and we could collapse onto the grass in our enclosure.

It was a lovely spot, with a view of the towers of the abbey across the water. With the last of our strength we extracted bread, cheese and sausage from my pack, and ate our picnic lunch in a prone position on our mats. This was followed by a restorative nap and gloriously hot showers.

Later, dressed in clean clothes and sandals, we strolled back over the bridge to investigate the abbey, and it was worth the trip.

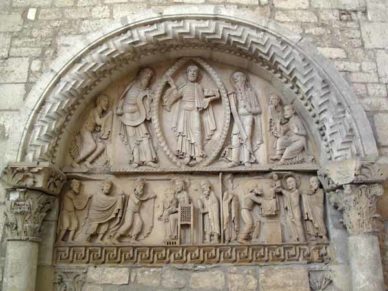

As we approached from the bridge, the great grey abbey building looked strangely lop-sided, with the grand portal on one flank of the tower and the dome behind out of alignment.

We found out that this was the result of a disastrous fire in 1559, which destroyed the other tower and much of the body of the church, together with many of the adjoining buildings of the town.

The abbey was founded in the 11th century as an offshoot of mighty Cluny. The monks who came to construct it were housed four kilometres upstream at la Marche, under the protection of the lord, and when the time came to move to the new settlement, so did most of the population and commerce of la Marche.

The village and abbey thrived and became an important river port and an essential stop on the pilgrim way to Compostela (as it is today). It housed 200 monks at its height in the 12th century, and they were renowned for their hospitality – “la charité des bons pères” (the charity of the good fathers). In time the original name of Seyr gave way to the present one.

Being so richly endowed – la Charité was known as the “eldest daughter of Cluny” – it was a favourite target during the Hundred Years War and the Wars of Religion. After the fire of 1559 the town never fully recovered and the abbey went into decline.

At the time of the Revolution there were only a dozen monks living there, and the building was resumed by the state and sold off. A few decades later it was about to be demolished to make way for a road when it was saved by the wonderful Prosper Mérimée.

Mérimée, apart from being an archaeologist and a writer (he wrote “Carmen”, later made into the famous opera), was Inspector-General of Historical Monuments during the 1830s and was responsible for saving many buildings that are now considered jewels of French cultural history, such as in Carcassonne and Vézelay as well as here. He was too late to save Cluny itself, but la Charité-sur-Loire, almost as huge, gives the feeling of what it must have been like.

We wandered awe-struck in the cavernous interior, still breathing power although only partially restored. Outside, the emerald-green turf was punctuated by irregular lines of white stone, remains of buildings destroyed in the fire, and the great cloisters at the side were encrusted with scaffolding, the whole thing veiled like a nun in white cloth.

In the narrow streets around the abbey, tourists abounded. What space there was on the footpaths was taken up either with café tables or with trays of books.

La Charité-sur-Loire has a more modern claim to distinction as a Book Town (Ville des Livres), and every second shop seemed to be a bookshop. I looked longingly through the titles and could have bought a barrowload of books in other circumstances, when I would not have to carry them on my back for several hundred kilometres.

The later part of the afternoon was spent in blissful slumber on the shady grass beside our tent.

When we ventured over the bridge again in the evening, the heat of the day was still pumping out from the old stones of the abbey as we sat with our backs against the wall holding glasses of rosé.

We felt a comradely bond with the centuries of previous pilgrims who had passed through this town before us, mostly in far harder circumstances than ours.

For dinner we returned to the island and ate at a pizzeria which looked out over the Loire towards the abbey.

The wide stretch of water just below the bridge used to be a staging post for flying boats in the 1920s and 1930s. In those days it was too far for them to get from the Seine estuary to the Mediterranean without coming down to refuel.

Nothing as romantic as a flying boat disturbed the calm surface of the river as we sat with our pizza, salad and wine, but the whole scene was enchanting and we went to bed very satisfied with our second day’s walking.