Sunday, 22 July 2012

Distance 27 km

Duration 6 hours 45 minutes

Ascent 101 m, descent 111 m

Map 140 of the TOP100 lime-green series

A deathly silence pervaded the camping ground as we crawled out at 6:10 am.

The sky was tinted with pink and a light haze hung over the canal basin.

The wide expanse of grass was saturated with dew but we had taken the precaution of camping near a picnic table so we had somewhere to sit as we shivered our way through breakfast.

Keith’s leg was now red and swollen, but he took two strong pain-killers and pronounced himself ready to go.

Crossing back over the dry canal bed and the railway line, up into the slumbering town with its pencil-thin church steeple, we took the road to Épineuil-le-Fleuriel.

Not far into the countryside, we came to the cemetery, at the edge of which was a turn-off, just as the barman had said.

We would never have taken it except for his advice, as it had no sign, and seemed to be merely an access road to a few houses through the railway underpass.

However, before we got to the railway line we saw a tiny road going off beside the tracks. We followed it for a while until it ran into a bigger one at a level crossing, which we went over.

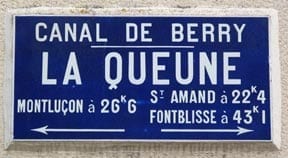

Here the bed of the canal could be seen as a depression in a ploughed field, and there was another tiny road heading in the right direction parallel to it, so we walked along for a while until we came to a cluster of rather substantial old houses, the hamlet of la Queune, and saw the canal suddenly full of water.

It was a pleasing sight, and we were also pleased to see GR signs again, having parted company with the last one somewhere near Faux-la-Montagne, more than a week ago. These ones were for the GR41, which we followed along the towpath of the canal for about an hour.

It was a very straight stretch and the grass on the towpath was thick and wet, soaking our shoes and making Keith go more slowly than ever. I could see that he was suffering, so I suffered too.

At the bridge of la Chapelle, the towpath was swallowed up by an impenetrable mass of nettles and bushes. The GR veered off on the road to the left, but we had our hopes of coffee pinned on the village of Urçay, to the right.

Having walked over flat riverside fields for a kilometre or so, we crossed the Cher and turned immediately onto a dirt track, hoping that it was the one marked with dotted lines on the map, which led into Urçay.

We came to a ramshackle farmyard and a tractor trundled out, driven by a weathered old woman, with a man and a tribe of children in the scoop at the back. They drove past us without a greeting, nor any sign of curiosity.

Luckily, the track continued beyond here and in due course we came to a few houses, soon after which we arrived in the streets of the village. We asked a woman passing by with an armful of branches whether there was a bar in Urçay, and she stood turning the question over in her mind for a nerve-racking age, before finally admitting that there was one, in the Place du Commerce.

We hurried on eagerly and got to the highway, where we saw a hotel/bar called le Lion d’Or (seemingly the name of choice in these parts – we had seen four or five in recent days), but it seemed unoccupied.

Then we noticed a group of shops in an enclave opposite, one of them with a red Kronenbourg sign indicating a bar. This was the Place du Commerce.

There were tables on the footpath outside, exposed to the sun but as the weather was mild we were happy to sit there.

The only other customers were a group of sapeurs-pompiers in full rig, having a break from some exercise they were doing across the square.

The woman in the bar advised us to go to the butcher’s shop for croissants – it doubled as an épicerie and a bread depot, while the bar was also a newsagent, a tobacconist, a pizzeria, a banking outlet and a taxi service. Such are the strategies for commercial survival in villages.

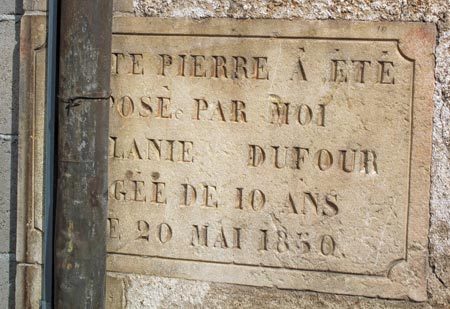

Basking in the multiple pleasures of the first coffee of the day, the croissants and the comfortable chairs (not to mention the aspirins for Keith), we noticed a plaque on the wall nearby, carved with the legend “This stone was placed by me, Melanie Dufour, aged ten years, on the 20th of May, 1850”. The date 1850 was just when the canal was in its heyday and no doubt Urçay was booming at the time.

Young Melanie, presumably the child of a local worthy, had the honour of inaugurating the new building. Some soulless latter-day plumber had laid a drainpipe over the stone, but it was still an affecting sight.

At the bottom of the square, a street led down to the bridge and we then cut off a wide loop of the river by taking a little road (the D178) over the rise.

We soon found ourselves in the picturesque village of la Perche, hanging as its name suggested above the river. It was full of flowers and also had a bar, beside the church, but we resisted the temptation.

With some difficulty we reconnected with the GR and plunged down into a morass of sand, pools and fences, part of a sand-mining operation. Here the GR signs vanished and it took us some time to struggle downstream to a picnic area and rediscover them.

At last we were back on the canal, or rather on the towpath. The canal itself was dry again and its bed was a tangle of weedy growth.

Half an hour later, as we approached Ainay-le-Vieil, we saw that some enterprising farmer had cleared the canal bed and planted a crop of hay, which had just been harvested.

With hopes of another round of coffee and a rest for Keith’s fat, angry-looking leg, we took the road into Ainay-le-Vieil, but all it had to offer was a château.

Back on the canal, we came to a short “pont-canal”, where the towpath and the dry canal bed bridged a stream, and soon afterwards there was a much longer one over the Cher.

We have never got over our admiration for the ingenious feat of bridging a river with a canal, a sight that we first saw years ago in Moissac. Indeed we admire the whole bold enterprise of the digging of the canals and find them charming, even in their old age.

On the other hand, it was delightful to see the river flowing freely below us, with its swirling rapids, its sandbars and beaches, after the man-made constraint of the canal.

Once over the pont-canal, the GR turned away up a hill, but we stayed on the towpath, hoping it would continue. The canal was dry and weedy but not completely overgrown, and there were shady trees to walk under.

A couple of kilometres further on we had the pleasure of seeing the water return, with all the flowers, reeds and insects that went with it. Despite this, things were getting very hard for Keith. His leg looked terrible and he trudged along in grim silence, staring fixedly ahead.

In the distance we could see a bridge, and when we reached it there was a beautiful sight – a large new restaurant on the canal bank, full of people enjoying Sunday lunch on the shaded terrace. We were in the village of Drevant.

It was about 1 pm by this time but we were too tired to be hungry, so we went inside and collapsed at a table while the waiter brought us coffee. The mere sight of the diners, the umbrellas and the pleasure boats on the canal had a reviving effect.

We knew that we only had four kilometres to go along the canal to reach our destination for the day, the camping ground of St-Amand-Montrond. We set off again, not exactly with a spring in our step, but at least with renewed determination.

Before we had gone more than a few steps past the restaurant, we were astonished to see great towering pieces of ruined masonry on the other side of the canal. It turned out that they were the remains of a large Gallo-Roman religious centre, with an amphitheatre, baths and a sacred spring.

We dealt with this last section by counting down the time, 13 minutes per kilometre, allowing for our slow pace. With each kilometre our excitement rose and as the canal began to veer to the right we knew we were close.

It kept curving around and around, as if trying to make a complete circle (although it was actually only a half-circle), but at last we saw houses on the other side and recognised the flags at the gates of the camping ground. With a glorious sense of victory, we entered the gates.

The place was crowded, more so than it had been the previous year, and yet the little snack bar which had been such a godsend to us had disappeared. However it did not matter, as we had made up our mind to eat in town, at the same restaurant as last year.

We found a good spot for our tent next to a high stone wall that looked much older than the camping ground, under a chestnut tree.

By this time Keith could hardly walk at all and even getting to the site was an effort. It was too late for lunch (after 2 pm), even though we had generous slabs of meat and bread left over from last night’s dinner.

After a shower and a change of clothes, we settled down for a blissful afternoon of sleep and reading.

By 7 pm, Keith had rallied enough to contemplate the walk to town, which we knew was about a kilometre.

We set off at snail’s pace and as we emerged onto the road, there was a queue of a dozen camper vans waiting to book in for the night. We wondered whether there was some big festival on, but there did not seem to be.

Once through the quiet, treeless back streets, we came to the statue of Jacques Brel and turned into the main square. The Office of Tourism was closed, but our chosen restaurant, the Massilia, looked promising for later.

We sat down at a bar in the square and ordered apéritifs. Poor Keith’s ankle had swelled to twice its normal size and was a rich plum red. It ached and throbbed so much that he was quite distracted. By some oversight we had no painkillers with us, so I galloped back to the camping ground and got some, surprised at how easy it was to run a couple of kilometres. A month on the track had toughened me.

When I got back, the waiter was packing up the chairs around Keith. I swallowed my rosé and we moved to a bench near the fountain to wait for the pills to do their work. They were strong pills but it took a good while.

Eventually we moved to the Massilia, choosing a table away from the open door, as it was getting chilly. The little man of last year was still making pizzas, twirling the discs of dough in the air, deftly decorating them and plunging them into the red jaws of the oven.

A stream of take-away customers passed through, but the tables were also well occupied with serious diners like ourselves.

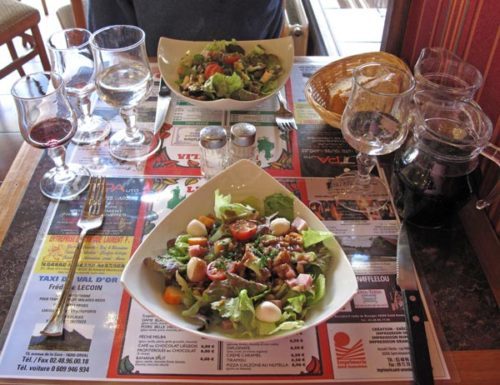

We had the menu of three-courses for €16. To begin, we had a Caesar salad and a salade auvergnate (with blue cheese and walnuts).

Meanwhile we talked about what we should do next, given the state of Keith’s leg. Various crazy ideas came and went before we thought of the most obvious one – calling a halt to the whole walk. Although I had suggested it earlier, Keith had never really considered it until that moment.

Our original intention was to walk on to Dun-sur-Auron, then along the other branch of the Canal de Berry as far as Mehun-sur-Yèvre. But by getting to St-Amand-Montrond, we had succeeded in joining up the loose end on the map from Lacelle, and there was no need to do more.

With this realisation came a great wave of relief – our walk was over for the year. We decided to catch the train to Bourges the next morning and see what transpired after that.

By the time the second course arrived, we were in festive mood. Keith had steak of course – how many cattle had died for him this year, I shudder to think – while I had crumbed veal. Both dishes were accompanied by a golden gratin dauphinois, and washed down with local red.

We finished with crème caramel for Keith and coffee icecream for me, most of which I passed over to him.

The walk back to the camping ground, while slow and laborious, was free of the worry that had been bothering us for the last week, and we felt a great sense of relief.

Leaving Saint-Amand-Montrond

Saint-Amand has a railway station. From there you can go to almost anywhere in France.