Monday, 24 June 2019

Distance 25 km

Duration 6 hours 15 minutes

Ascent 471 m, descent 310 m

Waking early, with the busy chatter of the dawn chorus in our ears and the thought of breakfast on our minds, we left our lovely high scenic room and walked the few steps to the bar.

We had asked yesterday and had been told that the bar opened at 6:45 am, but when we arrived at that exact time it was already going strong. We sat inside, as monsieur had not yet carried out the tables and chairs to the terrace.

As the boulangerie across the street seemed to be on holiday, we brought out some rolls that we had removed from the breakfast table at Liginiac, together with some butter and jam, which made quite a good accompaniment to our two rounds of coffee.

The barman’s daughter, a large girl with the same build as her ex-rugby playing father, emerged from the back and hurried off to school, while the rest of us relaxed over our hot drinks.

Setting off eventually, we took the D36 to the west. It was a narrow little road, bordered with wildflowers, and overhung by a glowing green forest. There were very few cars on it, and we descended gently beside a nameless stream until we came out into cleared land at the tiny village of Ydes-Bourg.

Passing a couple of lovely old stone houses, we arrived at the church, which was set among lawns with its shingle roof gleaming in the sun.

The circular eastern end and the bell-wall are apparently typical of the style popular in the Auvergne in the twelfth century, before Gothic had spread to the provinces, and to us this church was a most beautiful and uplifting sight.

These sorts of unexpected discoveries are part of the reason that we are so addicted to walking in France.

Beyond Ydes-Bourg, the road meandered downhill through fields, and after about forty-five minutes we we crossed a highway and found ourselves on another bit of the same abandoned railway line that we had walked on yesterday on our way to Saignes.

Like yesterdays’s section, it was a Voie Verte – a cycle path – so we set off briskly along it, with the houses of Largnac just above us through a hedge.

Having passed the former station building of Largnac, we crossed a river on a long, curved, dizzyingly high railway bridge, with niches built into the masonry as bolt-holes to retreat to if a train arrived.

Shortly after that the path became a corridor of ribbons and other hangings in exuberant colours, part of some local arts festival, we gathered.

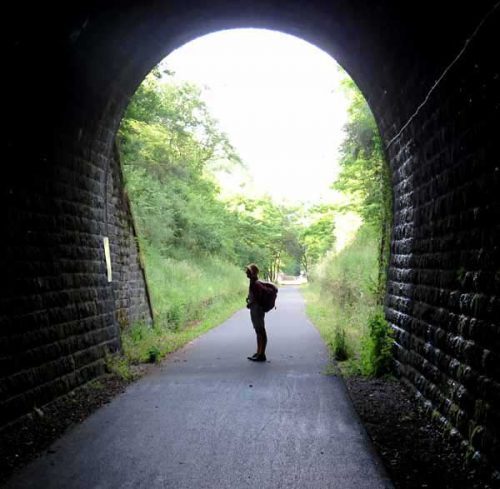

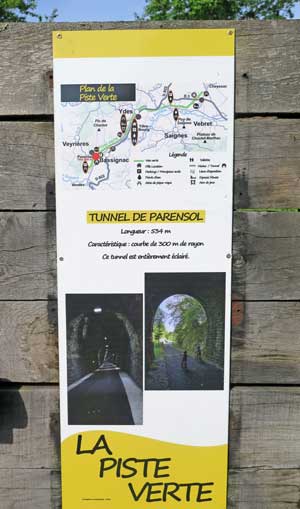

These kept us cheerful company until we came to the mouth of a railway tunnel, which walkers were advised to circumvent by taking the road above, whereas cyclists could go through. Naturally, we took no notice of this and plunged into the tunnel.

It was about half a kilometre long with a wide curve.

The road surface was newly laid bitumen and there were overhead lights all the way, so it was hard to work out why it was not thought suitable for walkers.

We remembered other tunnels that we had walked through, where we had stumbled through pot-holed mud in pitch darkness, with water dripping on our heads.

Emerging into the warm sunlight, we soon came to a complete and final barrier, and were diverted from the Voie Verte, onto a road. (Beyond this point the railway crossed the valley of the Sumène on a long viaduct that was apparently quite unsafe, and it certainly looked ricketty when we saw it later from below.)

We walked down to the floor of the valley, on a bike path beside a small, steep road, heading for the village of Vendes.

According to our map, there was a bar in Vendes, but unfortunately it had died since the map was made, and no amount of cursing and fretting brought it back to life. It was about 10 am and we had been walking since 7, so we felt a bit cheated.

From here we could see the railway viaduct strung overhead in all its decrepit majesty.

We passed under it just before it vanished into another tunnel.

We then had to regain all the altitude that we had lost on the descent to Vendes.

Initially we took the D12 and then a smaller road, which took us up to the charming hamlet of Jaleyrac, with its row of cottages smothered in roses, an old communal water pump and the stone church with its moss-covered roof.

For lack of anywhere else to sit, we occupied a set of steps in front of a house, only to have the door open and several women emerge.

They were most hospitable and insisted that we stay there, and would we like more water?

Here we ate the two paté-and-salad rolls that were all that remained of Alan’s sumptuous lunch packet.

From Jaleyrac we had a lot more climbing to do.

We continued on the road for a short time and then took a rocky track in a tunnel of trees beside a field of wheat, where we exchanged greetings with a farmer on his tractor, who was risking his life in an impossibly steep field. We expected to see the tractor overbalance at any moment and crush the poor fellow, but it did not happen while we were passing.

After a kilometre we came out into rising pastureland, at the top of which was the village of Bossières – hardly more than a collection of huge metal farm buildings, although there was the odd handsome old house as well, but naturally no bar.

We kept walking and in no time had crossed the highway, the D922, on its arrow-like way to Mauriac. We also were heading for Mauriac, but luckily there was a tiny parallel road, almost a wheel track, that took us straight there. We were getting hot and tired by this time and before we set off on this last section we sat down, took our shoes off, and drank the last of our water.

As we began to descend into Mauriac, we passed a new-looking housing estate, unattractively lacking in trees or even gardens, before coming to the established part of town, with its heavy, serviceable buildings that reminded us of Ussel.

We were not sure whether the camping ground here had a restaurant, or even whether it was functioning at all, and as it was more than a kilometre from the centre of town, we were tempted to look for a hotel. However the woman at the Office of Tourism relieved our mind on the matter of the camping ground (she said it was 4-star), and we decided to go there.

Somehow or other as we walked down the canyon of the main street, we did not find a single bar that we liked the look of. The afternoon was unpleasantly hot and there were no shady terraces visible.

Suddenly we found ourselves out of the houses and on a twisting country road, descending fast in the direction of the lake and the camping ground.

As promised by the helpful soul at the Office of Tourism, the camping had all the amenities – beautiful grassy pitches with shade (many already occupied), magnificent showers, an épicerie, and a brasserie a short walk away, on the lake shore.

Our host, Jean-Claude, suggested that we set ourselves up and have showers before coming back to pay. When we did, we bought a couple of tins from the épicerie, to guard against having to have muesli for dinner some day in the future, as had happened to us occasionally on previous trips.

Then Keith noticed an electric scooter by the door and Jean-Claude invited him to try it. It was amazingly powerful and Keith shot off like a bullet up the hill, returning drunk with speed and declaring that he could not live without one.

The next pleasure was dinner at the brasserie, which was every bit as delightful as we had hoped. The wide terrace, looking out onto the lake, was full of tables, chairs and umbrellas, and surrounded by wisteria and pots of flowers.

There were two young men and an older one at one of the tables, and as we walked up the two young ones sprang to their feet. I asked one of them whether he was the résponsable, and he answered with a laugh that they both were, or actually they were the irrésponsables.

Nevertheless, they took our order and delivered our meals impeccably. We each ordered a single course, with the usual accompaniments of wine and bread.

Keith had his unvarying steak, and I had a lamb chop, which turned out to be four lamb chops. Keith had to help me out with one of them.

We had the choice between mashed potato with cheese, and gratin dauphinois.

Keith chose the former, which turned out to be the wonderfully rubbery mountain dish called aligot, and I chose gratin dauphinois, which was merely boiled potatoes sprinkled with cheese, not the most impressive example of its genre.

Both plates were prettily garnished with salad and we enjoyed everything about the meal – the food, the surroundings, and later the company.

The older man was still sitting nearby, and presently he was joined by a blowsy woman towing a dog on a lead, evidently a local like him.

The dog began by putting its foot in his bowl of water and sending it flying in all directions. We all laughed, after which we fell into conversation.

He had been everywhere, he claimed, mostly to Asia, but never as far as Australia, and he was amazed that an English-speaking person could actually communicate in French. He was especially impressed when I said “en particulier”, not realising that it was almost the same expression in English. Anyway, deserved or not, I felt very pleased with his praise.

Previous section: Giat to Saignes