Saturday, 29 May 2004

Distance 30 km

Duration 7 hours 30 minutes

Ascent 1001 m, descent 838 m

Map 50 of the TOP100 blue series (now superseded)

Topoguide (ref. 700) Le Chemin de Stevenson

Breaking one of the golden rules of walking, we slept in and did not leave the camping ground until nearly 8 o’clock.

By some miracle we found the starting point of the Robert Louis Stevenson Track, the Rue Bessant, merely by wandering around near the cathedral, and then it was a simple matter of following the GR markers.

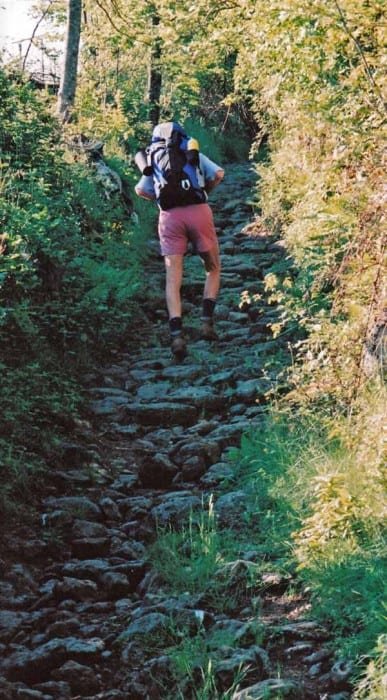

Of course the first section was uphill – everything is from le Puy – through prosperous streets and then up a steep cobbled way lined with bushes, which used to be the main route to the village of Ours. No doubt Robert Louis would have come this way from le Monastier during preparations for his travels with a donkey, to have his sleeping bag made in le Puy.

We had only descended a little way past the houses of Ours when I realised that I had lost my hat, the “fameux chapeau jaune” that had been my companion on so many trips. I feared that I had lost it far below in the streets of the town while taking off my jacket, but after a short mental struggle I decided to go back, leaving Keith with the packs at a water trough.

A minute later I met a pair of walkers coming towards me and before I could even ask, they said that they had found a yellow hat on the track, just at the entrance to the village, and had put it on a stone. I thanked them joyfully and sprinted over the rise, where my lovely hat was waiting for me, and I was back with Keith four minutes after I left. It was a promising start, or not, depending on how you looked at it.

We continued on our way at a great pace, passing the other couple and forging on. Apparently this path used to be the traditional trade route between le Puy and Avignon.

The plateau is dotted with mounds like giant molehills, covered with twisted pines. They are twisted, not because they are a different species, but because they were lopped mercilessly in former times to provide wood for bakers’ ovens.

The many bends and turns of the track were easily negotiated with the help of the red-and-white markers and before long we descended to the Loire at the village of Coubon. Even this far upstream the river was substantial and the bridge had often been swept away by floods in the past, most recently in 1980.

Close to the water was a bar, where we had our first coffee of the day, always a happy moment. It was made by a bemused youth who was not sure whether a grand crème was a coffee or an ice cream.

Afterwards we bought some cheese and tinned fish at the shop across the road and the shop woman showed herself a true heir to the costive, distrustful peasants that RLS had encountered. Our loose money was one cent short of the price and she glared at us and shook her head. We tried not to laugh as we handed over a €50 note.

Meanwhile the other walkers had come past again. We overtook them on a steep climb and the woman grinned and gasped ruefully that she was saving her strength for later. I felt that I should do the same, as the little blisters I had noticed on our last day in Burgundy were now a good deal worse.

We stopped for lunch in a pine forest and by 1:30 we were in le Monastier, where we intended to stay for the night. It consisted of a single canyon-like street clinging to the hillside, lined with dilapidated houses.

We stopped at a small pavement bar for a second round of coffees, then pressed on in search of the centre of town.

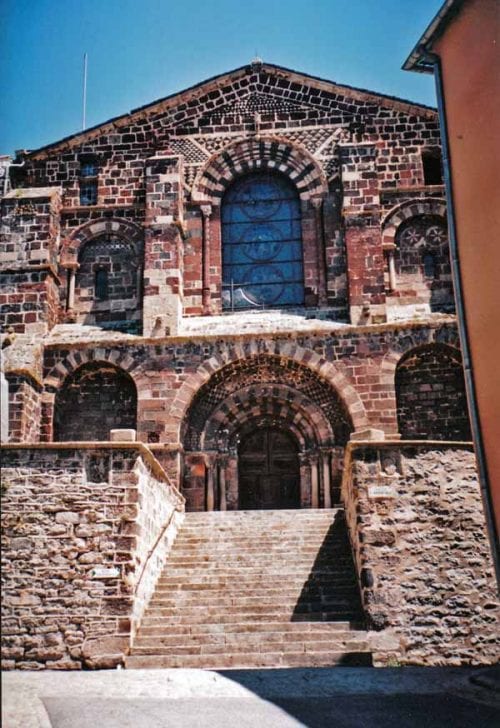

This also had seen better days, although the church was handsome in a dark volcanic way, and the view from the square, of range after range of blue mountains, could not be faulted. The town looked as though little had been either built or maintained there since Robert Louis set off with his donkey in 1878, except for the large statue reminding us of this fact.

The camping ground was below the town, down a plunging slope, and when we got there it was a study in desolation. Rank grass half-covered the shabby plots, the shower block was locked and full of dead leaves.

We had not taken into account the possibility that it would be too early in the season. However, it was only 2 pm and there was another camping ground at Goudet, ten kilometres further on.

The next section was a former stone-paved road, now eroded into an ankle-spraining rockfall, ascending sharply in a tunnel of trees, but we felt lighter with every step that we took away from the decrepitude of le Monastier.

Through woods and fields, we traversed the plateau. Both the near and the far landscapes were charming, but I was beginning to be bothered by my blisters.

This was the price I was to pay for not softening up my boots before we left home, another golden rule broken.

Past the church of Saint-Martin-de-Fugères with its fine bell wall, we took a farm road where a young chap was mowing a field under the critical eyes of two of his elders.

Then we came down steeply through pines towards the Loire and the village of Goudet reposing on a wide bend of the river.

We could see from above the camping ground beside the beach, with the gate open and flags fluttering, a reassuring sight.

We walked in past the Hotel de la Loire, where Robert Louis had stayed, and noted approvingly the blackboard menu propped outside.

At the camping ground an elderly couple, the owners, were sitting on the terrace. We were their first customers of the season.

While they dashed about preparing the shower block, we chose a daisy-strewn plot surrounded by low hedges and established our camp. We congratulated ourselves for having reached such a good village. The showers were still cold when we had finished, so we retired to the hotel for a drink.

The new owner, from Marseille, had only been in possession for two weeks and was presently over at his other hotel, seven kilometres away at Costaros. We found this out from our fellow occupants of the terrace, who turned out to be his relatives. They were minding the bar for him, but did not seem capable of getting us a drink.

When the owner came back, he distractedly served us a glass and then announced that he was closing up for the evening, as he had to go to his other hotel. He did not seem to be enjoying his new life as owner of two hotels.

Although this was a blow to us, we also had the possibility of eating at the gîte, which the old lady at the camping had recommended, as they used local farm produce. The only trouble was that the gîte was closed too. The people there were most apologetic, and aghast that the hotel was shut.

Our last chance was the roadside café over the bridge. Some trippers were drinking there in the evening sunshine and we joined them. They were from Montpellier and, like the Marseillais, were astounded to meet people from Australia. The manageress refused to believe that the hotel was closed, so she rang Costaros, only to have our story confirmed.

She was mortified at this display of heartlessness. We detected some local hostility, as at the gîte, to the interloper who had bought the hotel. Although they did not normally serve food, her bent old husband offerred to make us a ham baguette each and, with the addition of a carafe of wine, we had quite a pleasant little meal.

We strolled back to our tent, looking forward to a hot shower before bed. Keith went first and got a gush of painful boiling water followed by relentless cold. Our hostess came by and Keith became fluent enough to say “non chaude!”, which brought on a passionate display of horror and apology.

During the night, as we lay unwashed in our little tent, we were woken by some strange thuds and discovered a fox dismantling my pack.

It had already taken the bread and was tearing the cheese packet to pieces on the grass. It backed off reluctantly when I menaced it, but was soon trying again. This time it dragged my whole pack from under the flap and was shaking it violently and pulling it towards the woods, but after a short tug of war, I won. The rest of the night was rather cramped as we shared the inner space with our packs.