Tuesday, 4 July 2006

Distance 12 km

Duration 2 hours 35 minutes

Ascent 58 m, descent 51 m

Map 28 of the TOP100 blue series (now superseded)

We slept in slightly, ate our muesli in the fresh sunshine on the river bank and did not get moving till 8 o’clock.

Saying goodbye to the sturdy horse and its owners, we went back to the towpath, where a lovely old canal boat was moored, another echo from the Wind in the Willows.

Most of the boats on the canals were slick new powerful things, so it was a delight to see this old one.

It was only a short walk to Pousseau, where we were confident of morning coffee, but we were disappointed.

On the bright side, however, there was a sign advertising a bar at lock 50, so we set off cheerfully enough under the overhanging shade trees. Then we emerged into the open fields and the sun came out fiercely.

We passed a fortified farm, in which all the windows were arrow slits, reduced from its earlier glory as a Carthusian monastery. Then the river looped around at the base of a rocky bluff. Hot and thirsty, we arrived at lock 50 to find the café a mouldering ruin.

There was nothing for it but to plod on, but soon the path crossed the canal and we were in shade again.

We entered the town of Clamecy in a tunnel of greenery, avoiding a nasty-looking industrial area on the highway which was visible through the trees.

The streets of Clamecy had recently been beautified with gleaming cobbles, setting off the old half-timbered houses to advantage, and the centre had become a pedestrian precinct.

In former times the town had been prosperous, as evidenced by the elaborately decorated facades. It was the centre of the trade in timber from the Morvan as early as the sixteenth century, when Paris began to run out of its own supplies of wood. Individual logs cut from the forests of the Morvan were floated down the Yonne and its various tributaries to Clamecy, where they were made up into massive rafts for the remainder of the journey to Paris.

The skill of the raftsmen is reflected in the town’s traditional summer sport, in which two men balancing on logs try to knock each other into the water with long poles. The good thing is that both contestants end up as kings – one is the Wet King, the other the Dry King.

We found a charming bar at the top of the street, after having bought bread and pastries on our way up from the canal. From where we were sitting on the shady cobbles outside, every building we could see was leaning at a slightly different angle and half-timbered in a slightly different way. We were just near an overhanging corner of masonry under which crouched a small stone saint.

Up the lane beyond it was the Office of Tourism, where we got a brochure showing the sights and the camping ground, and we also found out that there was internet access at the café up the road called “Mon Oncle Benjamin”. This name recalls the nineteenth-century novel (now a film) written by one of Clamecy’s sons, Claude Tillier.

As we stepped in the door of this bar, we met the riverside philosopher of yesterday, who was as pleased to see us as we were to see him. We felt almost like locals. One of our emails was from the cycling Kiwis we had met last year, telling us they would be in Cosne-sur-Loire in three days’ time. We replied that we would be there in four.

We walked out to the camping ground along a narrow spit of land between the river and the canal. A notice informed us that the office would be unattended until 5 pm, so we made ourselves at home in the shade of a hedge and Keith went off to have a shower, returning indignantly soon after, as the ablutions block could only be opened with a code.

This was a level of bureaucratic stinginess that we had not met before. Fortunately the handicapped toilet was unlocked (probably by mistake) so we had lovely hot sponge-baths at the basin, leaving the floor awash.

After lunch we stretched out for a sleep in the shade. A gigantic Belgian campervan arrived, driven by a woman, and soon afterwards a wiry cyclist sailed in. He had ridden 140 km that day and was on his way to Lourdes, with his van-driving wife as the support team.

His solution to the lack of showers was to fill one of the concrete laundry tubs with water (cold), and huddle in it, like the crouching saint of the town, while his laughing wife videoed the scene.

Back in town in the late afternoon, it was too hot to breathe. Even sitting in a café was stifling, but after a while we bravely set off on the walking tour recommended in the brochure.

On the footpath we saw a wallet, so we took it to the Office of Tourism where we asked the woman to look in the phone book for the name in the wallet. The very first number she rang got the right person, a relieved and grateful girl, so we left feeling pleased.

On the tour we found out about another literary son of Clamecy, Romain Rolland, who won the Nobel prize in 1915. These writers of Burgundy were all passionate advocates of the common man, possibly because of that foretaste of the industrial revolution which was the logging trade.

This involved large-scale organised labour negotiating with middle men, even before mechanised coal-fired factories appeared, as the power was provided by the river.

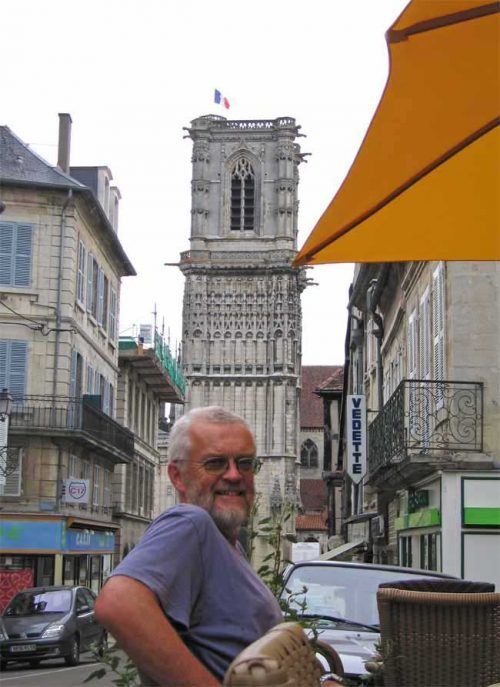

At the top of the town in a wide square was the church and tower, encrusted with finials, the building of which had cost the life of the master of works in an accident.

He is remembered by a statue, which is more than the rest of the dead workers got. The death toll on mediaeval buildings was generally high.

Across the square was an Italian restaurant where we had a fine meal in the open air. Starting in our customary manner by wolfing down all the bread and water on the table (promptly replaced), we had a shared salad, then pasta.

I had carbonara, which in France always has the egg yolk perched on top of the dish in a half eggshell, so you can mix it yourself into the creamy sauce. Keith had romaine, not quite as rich, and we disposed of the usual half litre of red. The total cost was €26.

The evening was cooling gradually like a switched-off furnace, and clouds were coming up. In the gathering dusk we found a bar where the semifinal between Italy and Germany was being shown and settled down to watch in a crowd of beer-drinking fans.

We left at the end of normal time (score 0:0) because lightning was flashing and thunder rumbling ever nearer. We picked our way along the narrow towpath which was weakly lit by some street lights on the other side of the canal. Then there was a flash and a bang and the street lights went out. Even more slowly we stumbled on, in light drizzle, and had to wander in a field of thistles before we found the entrance to the camping.

As soon as we were tucked up in our tent the rain fell seriously and continued all night, so we felt very lucky.

We did continue along the canal to its end, but only after a break of ten years.

Previous day: Châtel-Censoir to Coulanges-sur-Yonne