Wednesday, 26 May 2010

Distance 31 km

Duration 6 hours 45 minutes

Ascent 95 m, descent 119 m

Map 35 of the TOP100 blue series (or Map 135 in the new lime-green series)

Topoguide (ref. 6542) Sentier vers Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle via Vézelay

We had stayed the previous night at the Hotel Saint-Joseph on the main square of Sancoins. Before that we had camped every night since arriving France five days earlier, but Sancoins had no camping ground, which turned out to be a blessing, as there was a torrential rainstorm just after we entered the hotel, and the rain continued during the night. We greatly enjoyed our cosy room and the elegant evening meal in the dining room below.

In the morning the rain had stopped and the streets looked scoured and shiny. There was a market setting up in the square below our window as we spooned in our humble breakfast of muesli. It was not the market for which Sancoins is famous, the great beast market, held just out of town on the same day.

At 6:45 we crept downstairs and out through a side garden, then crossed several other squares until we found the D41 leading out of town in a diagonal direction towards the canal.

On the bank where we joined it again there was a fitness course, with instruments of torture such as chin-up bars, hand-swings and benches for push-ups.

There was something deeply wearying about it, from the point of view of people with packs on their backs.

We took ourselves off along the towpath, where the lush, wet grass quickly soaked our shoes.

It was easy walking apart from that, and after a while the GR crossed a bridge and climbed away from the canal to a scatter of houses and a large cross.

Leaving the GR momentarily, we continued down the road to the village of Augy-sur-Aubois, set in fields by a stream.

It was an appealing little place, with low cottages and a church around an irregular square. A little further on we came to the bar/épicerie promised in the Topoguide. One door led to the tiniest of supermarkets and the other to the bar, but they were part of the same room inside.

With our newly bought bread, cheese and croissants, we went through to the tables and had coffee. The same man served us both times, and his two little daughters took an interest in these oddly-dressed strangers.

One of them asked us whether we were going home and I said we were, but we lived at the end of the world, across the sea. This seemed to impress her.

We, on the other hand, were impressed that a young family would want to bury themselves in this tiny place, far from civilisation.

It later occurred to us that they were about ten minutes drive from Sancoins.

We took a side road to get back to the GR, then zig-zagged around sodden fields and past cottages straight from a Hardy novel, until we rejoined the canal.

On the towpath, a monstrous mowing machine came towards us, swallowing weeds and wildflowers and leaving a lawn in its wake. The driver courteously pulled to the side to let us past.

At Liénesse we passed the remains of the Maison-Dieu, the ancient pilgrim hospital, and on the opposite bank was the château of Liénesse with its round pigeonnier.

We sat on a low wall for a drink, then crossed the bridge and continued on the towpath. The first part was actually a wheel-track, as all the lock-keeper’s cottages along the canal (now charmingly renovated) were occupied.

After a few more kilometres we came to another nineteenth-century engineering curiosity at Fontblisse – the branching point on the Canal du Berry.

The branch canal went off through a lock in the direction of Vierzon, on the river Cher.

Past that point, the towpath got ever more overgrown until we were wading in wet grass up to our waist.

Somewhere here I lost my spectacles when I leaned over to retie a shoelace. They must have fallen out of my pocket, but luckily I had brought another pair.

We were pleased to get to the road bridge at Vernais, where the grass was mown and we were able to sit on a bollard and eat a muesli bar and some chocolate, the last of our snacks from the plane.

From there it was only four kilometres to our destination, Laugère, where there was a hotel. Or so it said in the Topoguide. It was called the Faisan Doré, and we saw it immediately beside the highway, but when we went there, we were told that it was only a restaurant these days.

It had not been a hotel for at least five years, which was annoying, since our Topoguide was supposed to be a new edition only a year old. The woman at the bar suggested a chambre d’hôte just over the canal.

We entered a large garden enclosed by a hedge and knocked on the door. After a long pause, a whiskery old gentleman opened it with a shaking hand, peered out and decided we were suitable people to be shown a room. Halfway up the stairs, I asked the price, and a minute later we were out in the street again. €75 was too much to contemplate for people who were used to paying €10 at a camping ground.

The only other possibility was the gîte d’étape at Charenton, half an hour’s walk further on. We no longer had confidence that it would exist, and we were worried about getting an evening meal there, so, although it was already 1:30 pm, we went back to the Faisan Doré for a late lunch.

Most of the diners were having dessert or coffee when we sat down. It was a fixed menu – soup, blanquette de veau, cheese and dessert – and we found that we could not eat that amount in the middle of the day.

Most of the veal ended up in the goat-cheese container that Heidrun had given us in Cosne-sur-Loire.

A short canal walk took us to a road, and that took us past a raw new housing estate into the old part of Charenton, which was at the other end of the spectrum – positively black with age.

All the shops in the deserted main street were boarded up or closed (admittedly it was 3 pm, not an hour when French villages are at their liveliest).

Near the church we asked a pair of women for directions to the gîte, and they both confidently pointed, in opposite directions. Eventually the younger woman deferred to the bent, blind older one, who turned out to be right.

We continued to a wide semicircular square with pleasant gardens, a bar and a boulangerie. With the help of these shopkeepers we found the gîte in a fine old house just opposite, and knocked, but there was no reply.

It was starting to rain so we retired to the bar, a rather dark, austere room, and drank coffee in the company of a few local layabouts and the barmaid.

While we were there we saw a strange sight – a walker pulling a little cart made from two poles joined to a wheel, on which his possessions rested. Draped in a rain cape, he trudged tiredly into the square and sat down on a bench.

Presently Keith ventured across the square and knocked again at the gîte.

Nobody answered, but a small car that was driving past suddenly braked and reversed into the driveway. It was Mme Mativon, the owner.

She told him that she charged €25 per person for dinner, bed and breakfast, which seemed eminently reasonable. Keith indicated that there were two of us and she told him to come back in ten minutes.

When we did, the front door was open, her bag was lying on the floor but she could not be raised, even when we wandered through the garage and into the enormous park-like back garden.

At long last she appeared and was horrified to see it was not two men but a couple that she was receiving. She had assumed that the pilgrim with the cart was Keith’s companion, and had made up a room with two single beds.

To get rid of us, she gave us the key to the church and we dutifully went to inspect it while she prepared a double room.

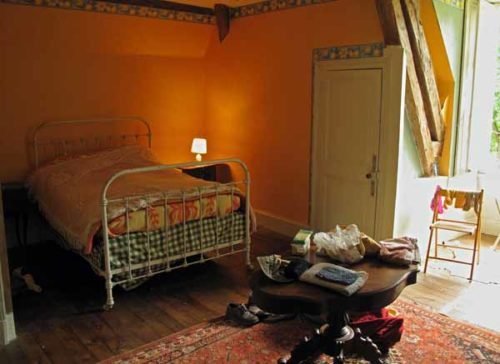

Having raised her again with an effort, we followed her upstairs along a gloomy corridor to our room, which was large, dusty and ramshackle, with a soft, sagging bed and a shower in an untidy cubicle. Nevertheless it had a provincial charm.

Dinner was downstairs in madame’s kitchen. To reach it we walked through a big glass conservatory looking out onto the park, where we expected to see deer and peacocks.

She was no chef but we had a substantial meal of thick soup, a quiche and strawberries loaded with sugar and liqueur. She ate with us and talked the whole time.

She had lived in this house all her married life, and her husband’s family owned great swathes of farmland in the district. He had died two years ago.

She said that her busiest months for pilgrims were April and May – it was a long way from here to Compostela, and July was the right time to finish the journey.