Friday, 29 June 2007

Distance 29 km

Duration 6 hours 35 minutes

Ascent 412 m, descent 479 m

Maps 59 and 58 of the TOP100 blue series (now superseded)

We crawled out, shivering and unrested, into the dawn. Mist hung over the river as we ate our plain muesli, with our sleeping bags draped around our shoulders.

We packed hastily, keen to be on our way and get some circulation going, but no matter how fast we walked we never warmed up in the hour and a half it took us to get to Ispagnac.

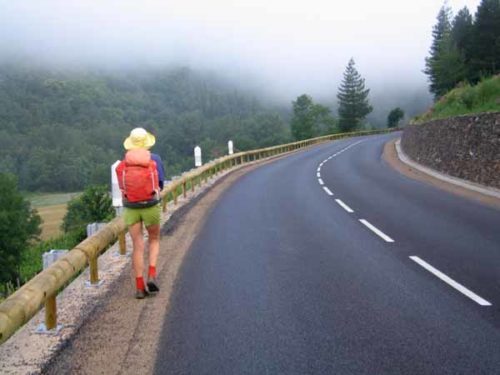

The walking track was on the other side of the river, and as there was no bridge at this point, we had to take the highway, which luckily was almost empty at that hour. To get to the walking path, we would have had to go back to the bridge at Florac itself, adding about three kilometres to our journey.

After forty minutes hurrying along in the perishing cold, we turned off on the small road to Ispagnac, closer to the river. In due course we passed the first old bridge, and soon afterwards arrived in the centre of the village.

We bought some bread and pastries and dived into the nearest bar, as far as possible from the door, where hot coffee and pains aux raisins did what a ten kilometre forced march had not done – it warmed us up.

Emerging from this cosy cave, we admired the oddly-shaped eleventh-century church nearby. We are always impressed by anything older than the twelfth century, the age of the great pilgrimage expansion.

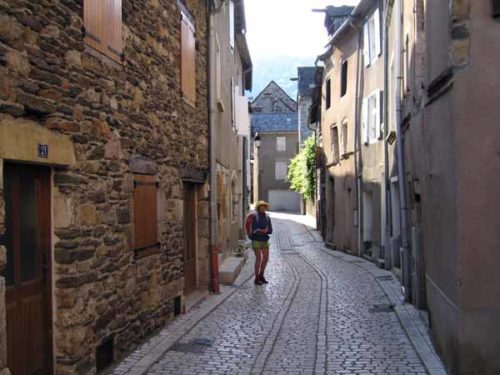

Around the corner was the former main street, the Rue des Barrys, still solidly cobbled, going between the now vanished fortifications.

The tall houses had pulleys at the top to haul large objects up, and between them, low arched tunnels, known as boltes, led off into courtyards lined with houses, little communities in themselves.

At the end of the street we picked up the green and yellow markers of the Sentier des Gorges du Tarn, which we would follow sporadically for the next three days.

Leaving the village, we passed the camping ground and a field full of horses (preparing for an endurance trial tomorrow), and crossed the Tarn on a footbridge.

This elegant hump-backed Gothic structure was given to the town in the fourteenth century by Urban V, one of the Avignon popes, who was born just up the river near Pont de Montvert, and was no doubt responding to an appeal from his childhood community.

Once over the river, we traversed the one and only street of Quézac and continued out into the fields. After a kilometre or so the road degenerated into a stony track, which plunged along the steep, forested slope above the river.

The gorge closed in around us as we clambered up and down on the hillside. At length we came to a side valley with a road twisting down from the causse to river level.

Here there was a holiday camp for school children, reminiscent of a military barracks or perhaps a minimum security jail, with a few bored looking kids hanging about.

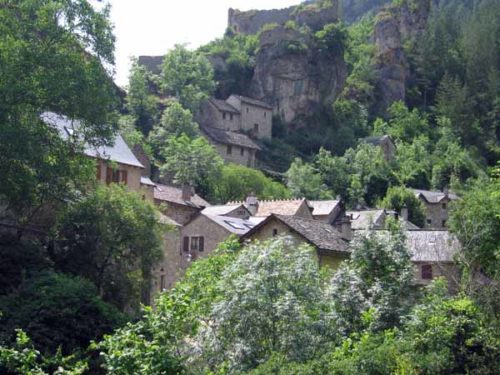

Higher up we could see the perched village of Montbrun, looking as isolated now as it must have been in previous centuries.

There is now a bridge connecting this little road with the main one on the northern side, which was opened in 1905. Until then, the gorge was only negotiable by barge, or by the sort of mule-tracks that we had been following.

Our road continued for a few more kilometres beside the water and we never saw a single car in motion on it.

We stopped at la Chadenede (half a dozen houses) to rest under a tree and eat our pieces of cheese rescued from last night’s dinner, with the bread from Ispagnac.

A bit further on, the road suddenly ceased to exist, and we found ourselves entering the hamlet of Castelbouc.

The first thing we saw was a monstrous boulder, on top of which the ruins of the château stood like rotten teeth. Beneath this was a cluster of well-tended cottages, many of which were built into the rock itself.

A neat pathway wound between them over the bulging rock. To our modern eyes it was all movingly reminiscent of life in the pre-industrial age.

At the end of the houses there was a fork in the track, with no green-and-yellow sign to guide us, but we guessed the way was to the right, towards the river, and this proved correct.

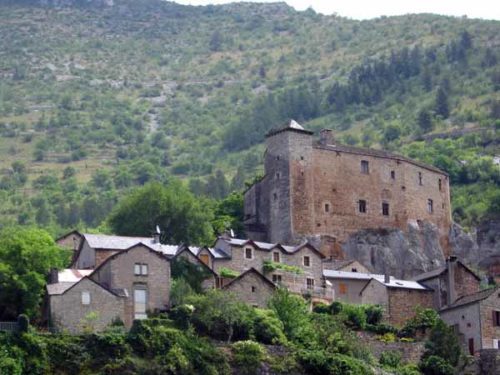

We kept close to the wooded bank of the Tarn until we came level with Prades, a village on the other side backed by an uncompromising fortress, with a spillway across the river, now exposed and walkable.

From this point the track climbed high above the water, although there was still plenty more height above us, and joined the ancient thoroughfare that had been superseded by the road. It was superbly constructed, with a drystone wall supporting the outer side and another one retaining the rocky upper slope, which had been chipped away in parts.

Generations of people must have worked on it, and even more generations got the benefit of it. The paved surface was now covered with dirt and debris, but it was still a splendid path.

It was easy to imagine the original inhabitants of Castelbouc hastening along it, on their way to the market in Sainte-Énimie. Meanwhile the river below described large curves between sandbanks, and the highway snaked across the opposite hillside.

Eventually we descended to the river, where there was another school-children’s barracks, as well as a low bridge. The track became rocky and uneven, jammed between the water and an outcropping band of rock, and still in thick forest.

One more curve of the river brought us out unexpectedly onto a bitumen road, the one coming down from Meyrueis, and we crossed the bridge at an angle into a totally different world.

Gift shops, bars, hotels, kayak and canoe hire, signs, posters, cars and tourists crowded the concrete apron of the river front, while behind, the grey stones of the old village stood quietly.

It was 1:45 pm, so we hastened to the nearest bar for coffee, to celebrate our arrival. The waiter told us that the nearest camping ground in the downstream direction was a couple of kilometres further down the road, on the way to Saint-Chély-du-Tarn, although the woman in the Office of Tourism later said it was only one.

While we ate our second lunch on a bench near the river (it was our fourth meal for the day, after two breakfasts and a previous lunch), we formed a plan.

The walking track was on the left bank, across the river, and as there was no bridge between Sainte-Énimie and Saint-Chély-du-Tarn, we would tomorrow take the road as far as Saint-Chély-du-Tarn, and then cross over to the track, rather than retrace our steps up to Sainte-Énimie.

As we have found many times, walking on a road early in the morning is quite different from doing it later in the day.

We set off down the road. The only tricky part for walkers was a short tunnel just out of the town with absolutely no kerb, but we got through it without trouble. It was indeed two kilometres to the camping ground, which clung to the slope above the river in a series of terraces.

Everything was spick and span, with flowers and spreading trees. It also had a pool but it was far too cool to use it. At 6:30, dressed in our best (i.e. our other set of clothes), we returned to explore the old town.

In the charming barrel-vaulted church, there was a vase in a side chapel marking the height (40m) of the floods of 1900 and 1985.

The streets higher up had been exquisitely renovated and were empty of tourists, apart from the odd straggler like ourselves. We could see how it had got its appelation of Plus Beau Village.

Back in the busy lower streets, we did quick survey of the eateries before going to a bar for a glass of wine and to consider our options. We decided on the Restaurant du Nord, which had a €13.50 menu.

Out of habit, we sat outside initially, but we soon realised that we had made the same mistake as last night, forgetting that we were in the mountains, so we retreated indoors, where it was snug and lovely.

We began our meal with crudités and a goat-cheese tart, then shared a steak and a cèpe omelette. To finish, Keith had a crème brûlée, needless to say, and I had cheese, which I put away for the next day, also needless to say.

Previous section: St-Jean-du-Gard to Florac